[ad_1]

Tate Modern’s latest show opens with a king – the dein of Agbor in Delta State, Nigeria. Stately and handsome, he poses for his lifesize photograph in copious red robes that merge with his red velvet footstool and throne as if he were one with his royal role. In one hand he holds a pressed white handkerchief, as if against the heat (or the cares of office: this dein is known for settling disputes). The monarch in the next portrait sits upon a throne of stone, carved with long chains of cowrie shells. A third appears surrounded by gilded replicas of the Benin bronzes routinely displayed in European museums (give them back).

George Osodi’s dazzling photographs of Nigerian monarchs, of whom the west knows so little, were taken this century. When the British colonised parts of Africa in the Victorian era, hundreds of tribal kingdoms were merged to form the artificial boundaries of Nigeria. Yet the monarchs of these subsumed kingdoms continued to exist, as they do today. These portraits are a record of the present but also the past.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography presents Africa through its own lens. The art is exhilarating, dynamic, compelling, profound. It is a vital experience, just in terms of pure knowledge alone.

Here are girl biker gangs in Marrakech and gay picnics in South Africa, haunted Cameroonian landscapes and dense streets in the megacity of Kinshasa, Mauritanian migrants trying to reach the shores of the Mediterranean.

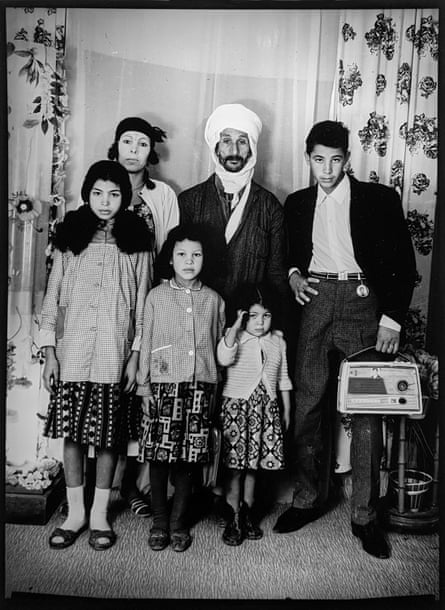

Lazhar Mansouri’s black-and-white photographs, taken in his village studio in north Algeria in the 50s and 60s, offer staggering glimpses of Bedouin and Berber sitters, some posing with radios, as well as villagers got up like Marlon Brando.

Given the population of Africa, now more than a billion, and the sheer number of images that might have been included, judicious selection was crucial. Some of the 36 artists in the show are justly famous – Samson Kambalu (last seen at Modern Art Oxford); Fabrice Monteiro, shortlisted for the Prix Pictet; the venerable James Barnor, whose joyous and uplifting studio photographs of post-independence Ghanaians were shown at the Serpentine Gallery in 2021. Others deserve to be far better known.

Angolan artist Edson Chagas’s fantastical photographs are posed exactly as if for a passport photo. But each sitter wears a highly expressive Bantu mask of the sort historically favoured by western collectors. Just to continue the point, Chagas devises a fictional name for each subject – Salvador Kimbangu, Pablo Mbela – European-African hybrids recalling Angola’s past as a Portuguese colony. Who is allowed to travel, these images appear to ask, compared to which favoured objects?

Chagas’s images are in a gallery devoted to masks, and what they mean in Africa as opposed to Europe. Zina Saro-Wiwa is showing a film alongside, in which she herself appears in a telling variety of masks that make her both more, and less, visible as a contemporary African woman. It ends with a phenomenal shock.

In Wura-Natasha Ogunji’s piercingly titled performance video – Will I still carry water when I am a dead woman? – a procession of masked women haul heavy water canisters along the ground through a district of Lagos. Men gape; women nod, taking photographs in recognition. At one point, in this unforgettable video, a local woman carrying an equally heavy load of liquid in the form of a basin of bottles balanced on her head, passes the procession without being able to turn for a second to look.

The show’s thematic groupings are always judicious. The spiritual section features Senegalese artist Maïmouna Guerresi’s marvellous five-panel polyptych showing an old man in a high black hat reading Sufi scriptures to four girls dressed in bright red, perched on black blocks round a table. They listen, but only while turning pensively towards the greater realities of existence conveyed through the shell case and the sinister petrol can lying on the table.

Cameroonian artist Em’kal Eyongakpa’s extraordinarily dark landscapes appear haunted by shadowy feet, ancient objects and even, in one shot, a spectral body: the traces of war lying in the land like smoke on water. And there are haunted photographs.

Sammy Baloji’s archival images of Congolese labourers, some of them chained, materialise within contemporary photographs of ruined mines; the industry now as dead as the forced labour. Angolan artist Délio Jasse’s eerie double exposures superimpose period bank and passport stamps, and government letters, over 60s photographs of a colonial Portuguese family. You search for some trace of Angola itself and find only one single black African face, inevitably that of a servant.

The show considers the camera as an imperial device throughout. I admired a strange conurbation spreading across the floor of a vast central gallery, composed entirely of dusty old box files. Grouped, stacked, felled, they form a low-lying cityscape, the architecture of modern Lagos. And one of these piles takes the shape of Independence House, commissioned by the British, and in which secret documents and photographs were concealed. Some of these boxes now lie open, revealing colonial photographs buried beneath the red and ochre soil of Nigeria. Ndidi Dike’s installation is mordantly titled A History of a City in a Box.

Photography is a means to so many different kinds of art at Tate Modern – massive Cibachrome prints, film installations, multimedia sculptures. A wonderful old-fashioned slide show, in the dark, sets up found photographs of 19th-century Africans in Victorian dress whose identity is sometimes hazy. Each is followed by a question. Are these really their names? What did they do for a living? What is the occasion? And, above all, are these portraits “evidence of mental colonisation” or did they challenge prevailing images of “the African” in the west?

Organised with so much insight, intelligence and sympathy by Osei Bonsu, Tate Modern’s curator of international art, this is a terrific exhibition. And what’s remarkable is the way that so many visions of such an unimaginably vast continent are united, here and there, in microcosmic detail. If only you look as closely as these photographic images encourage.

The woman carrying a great basin of drinks on her head reappears, in spirit, in emblem, more than once. And eventually in one of Andrew Esiebo’s colossal cityscapes of teeming Lagos, where pedestrians make their own walkways through the chaos, people park their cars on the highways and demolished buildings are propped up as shacks. There she is again, heroic, no longer just another figure in the crowd.

[ad_2]