[ad_1]

The park, which is in Markham, Ont., at the northeastern edge of Toronto, hugs the Rouge River and is the site of a major ecological restoration effort just steps away from people’s homes.

On a cloudy day in June, hundreds of volunteers were planting trees and shrubs in an effort to restore a barren part of the park.

In 10 to 15 years, they should grow up to 20, 30, even 50 feet [15 metres]. And it should look like a nice, thriving forest,

said Nishad Islam, environmental project coordinator at the Friends of the Rouge Watershed, which was coordinating the event.

And hopefully it’ll be home to a lot of endangered wildlife species, different types of turtles, salamanders as well.

Nishad Islam coordinates planting events at the Friends of the Rouge Watershed, and sees direct benefits for local residents near restored habitats

Photo: (CBC) / Inayat Singh

The Friends have a decades-long history in this part of the Greater Toronto Area, advocating for the nearby Rouge National Urban Park — the largest urban park in Canada, over 19 times the size of Stanley Park in Vancouver.

Many conservationists consider it one of the best examples of nature restoration in the country — home to 1,700 plant and animal species, 42 species at risk, a place where students learn to camp and people hike and picnic — while also being surrounded by millions of people in Canada’s largest metropolitan area with Highway 401, North America’s busiest, running right through it.

With restoration work, we are essentially just making it more of a natural bigger space for those endangered species to come, and as well as for people to kind of enjoy this beautiful area that we have,

Islam said.

The work here is part of efforts across Canada to restore nature and bring back biodiversity — as governments, communities and researchers realize the importance of green spaces in fighting climate change and preparing for extreme weather.

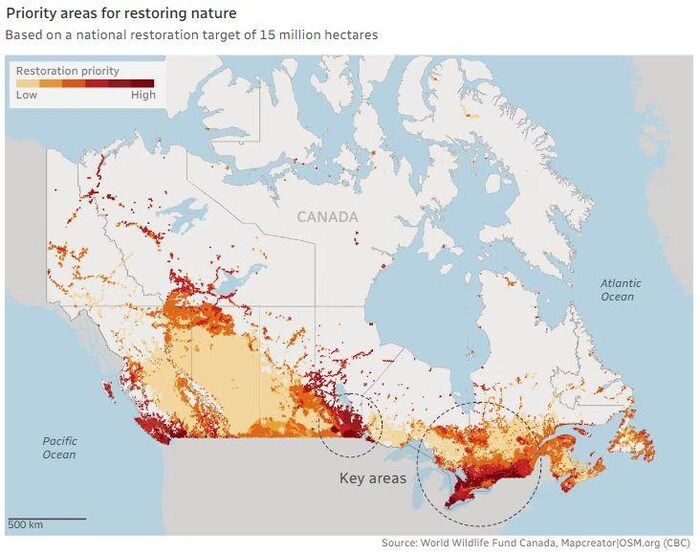

The work is backed by new research (new window) from the World Wildlife Fund that shows that areas of top importance for ecological restoration are also near where people live, especially in southern Ontario, Manitoba and Quebec.

Source: World Wildlife Fund Canada, Mapcreator|OSM.org

Photo: (CBC)

A global push to save nature

Unlike environmental protection, which involves establishing parks and conservation areas to protect natural areas, restoration involves going into degraded areas and planting trees and shrubs to restore the land, approaching what it once was before human activities changed it.

Restoration is key to Canada’s efforts to reverse biodiversity loss — now a part of the country’s international obligations, after the COP15 UN biodiversity conference (new window) which was hosted in Montreal last December.

Countries around the world reached a landmark deal to save nature and establish targets for protecting and restoring ecosystems, and observers want Canada, as a host country, to lead by example.

WATCH | How Canada can meet its ambition to restore nature:

Coming out of COP15 in December, we saw really ambitious goals and targets committed to by the government of Canada,

said James Snider, vice president of science, knowledge and innovation at WWF Canada and a co-author on the study.

But now that we have these ambitious goals and targets, we actually have to begin to implement them.

Using field and satellite data, researchers calculated carbon storage potential and benefits to biodiversity for the areas of Canada that have been transformed by humans.

The study considered three different potential restoration targets — from 5 million hectares to 15 million hectares (the latter representing a target of restoring 30 per cent of Canada’s converted landscapes). In all these scenarios, the most important areas for restoration were in southern Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba — also the places that have been modified the most by human activity.

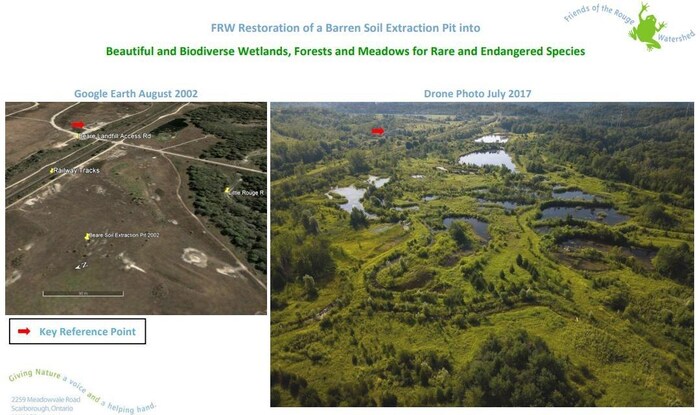

A before-and-after poster from the Friends of the Rouge Watershed, showcasing their ecological restoration work at a site in the eastern part of Toronto.

Photo: Submitted by the Friends of the Rouge Watershed

Snider says that means that restoring those areas have direct benefits for people, such as protecting water supplies, providing clean air and preventing floods.

It’s not only those people that live directly adjacent to those areas that benefit from having those natural areas, but more broadly the people that live, you know, throughout the region,

Snider said.

Finding land — and people — for restoration work

But the location of the tree planting event along the Rouge also showed the challenge of doing restoration so close where people live. The WWF’s analysis did not include urban areas with residential development, because it does not suggest displacing people for nature.

But getting access to land to restore can be challenge. Michael Petryk from Tree Canada, a national organization that helped organize the event in Markham, said groups like his have to get creative to find spaces to restore, since there’s pressure from the need to build more homes and farms.

Michael Petryk, director of operations at Tree Canada, hopes events like the tree planting at Tomlinson Park inspire people to take up this work in their careers and communities

Photo: (CBC) / Inayat Singh

Beyond that, he also pointed out that there’s just a shortage of skilled workers to do the restoration, something he hopes large volunteer tree-planting events can counter.

This is a great opportunity to introduce people to urban forestry, that it’s a career, maybe they can talk to their children about it, get people into it,

he said.

Restore the land and the species will come

Jill Crosthwaite works at another restoration project, at a small but ecologically crucial island in Lake Erie, about 400 km west of Toronto. Pelee Island is an important staging ground for migratory birds, welcoming over 300 species of birds during their travels.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada, a conservation group that acquires land to protect and restore it, has restored shorelines, forests and wetlands on the island.

Jill Crosthwaite, conservation biology coordinator for the Nature Conservancy of Canada, works on various restoration projects in southern Ontario, including on Pelee Island.

Photo: Submitted by the Nature Conservancy of Canada

If we’re working somewhere like Pelee Island, it’s got amazing diversity as it is. It’s got a lot of species that are quite rare and not found in many other places in Canada,

Crosthwaite said.

A lot of those species are really anxious for more habitat. So they’ll get in there and start using it quite quickly.

Crosthwaite said the NCC looks for lands close to important habitats — like forests and wetlands — and works to restore them based on what those nearby habitats look like. A lot of the land they work on has been converted by humans for over a century — but once restored, it can take just a year or two for animal and bird species to start moving back in.

There are many benefits to humans as well — known as ecosystem services.

Most importantly, restored wetlands hold rainfall and control the amount of flooding, and the plants in those wetlands help filter the water and clean out pollutants like fertilizers before it all flows out into the lake, Crosthwaite said.

The new habitats can also be places for people to visit.

That really gives people a place they can go and walk, they can get exercise, they can connect with nature,

Crosthwaite said.

They can see things that maybe they wouldn’t have been able to see.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada is restoring wetlands on Pelee Island to provide habitats for species.

Photo: Submitted by the Nature Conservancy of Canada

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Inayat Singh (new window) · CBC News · Reporter

Inayat Singh covers the environment and climate change at CBC News. He is based in Toronto and has previously reported from Winnipeg. Email: inayat.singh@cbc.ca

[ad_2]