[ad_1]

National Geographic Explorer Anand Varma points to something resembling a fish tank skeleton in a corner room of the lab. His office–or what would have been his office if he hadn’t considered using it as an aquarium–is coated floor to wall in ship deck paint. It needs to be water resistant.

“That’s mainly to house our marine species and aquatic animals. Although, we’re building some photography infrastructure into that.” He says it nonchalantly. He’s created an aquarium with far less before. His photography studio, which would also house various animal subjects from time to time, used to be his garage. Acquisition of this new space, a retired 1927 ketchup factory room he’s engineered into the WonderLab, means having a designated center to experiment with innovative ways of documenting wonders of the natural world often invisible to the naked eye, and helping shepherd others do the same.

Varma’s curiosity, experimentation, and passion are endless. Identifying professionally as a science photographer is “ambiguous enough,” he says, since he’s a biologist by education whose passion for photography has led him to a career of documenting the natural world. But through years of photographing a growing list of species–from hummingbirds to parasites–and their biological processes, he’s arrived at as many discoveries as he has questions.

Varma has always wondered how natural processes take place. What does it look like when a chicken is being formed in the egg? How does a hummingbird tongue work? The relentless pursuit of his curiosity has funneled into a life of creatively solving problems. If the technology that could answer these questions existed, he wouldn’t have to create it himself.

“I’m a supremely unqualified engineer,” he says with palpable humility. But around the WonderLab, which at the time of this interview houses around 40 tanks, 16 incubators, countless engineering tools, and bakery carts full of inventions, there’s evidence of his mind at work in every corner. To achieve this caliber of detail, everything must be specialized.

Synergy of science and photography

The WonderLab’s windows open toward San Pablo Avenue in Berkeley, California, in one of the city’s more beautiful industrial buildings. Varma envisions the space as a place to train a new generation of practitioners who can design their own techniques for cultivating curiosity and wonder. At this time, before officially opening its doors to students in the fall, the space is a work in progress. There’s a kink to workout with the window shades, which will hopefully be resolved shortly. There are also some LED lights coming in, that will dim things down to about point three percent around the lab when he needs. It’s all part of laying the groundwork, and this kind of time investment has yielded results for Varma.

“This is a system I built for jellyfish.” Varma stands in front of an enormous steel table he sourced from an optics lab that specializes in laser research. The slab appears to float in midair which helps isolate outside movement. “It means we can set up cameras to film really tiny things without any vibrations.” Old microscopes he found on eBay hook up to cables that, with some engineering, allow him to adjust motors and lights via remote control. “We can connect it to software that allows us to program movements and scene changes.”

To an onlooker, the desk-sized film studio looks like a Frankenstein robot, but he’s essentially duplicated a Hollywood stop motion film rig. It’s the same sort of technology used in Wallace and Gromit.

Varma reveals he grew up making clay stop motion films with his brother. He realized early on in his life that this type of animation could be applied to nature’s unseen world. He also remembers his fixation with the diagram of the lifecycle of a jellyfish in one of his biology textbooks. His thoughts went something like, “It does not make any sense how they transform across their lives. They go from stuck to the ground to floating in the ocean and have this weird in-between phase.” The fusion of his interests in visual media and science was beginning to crystallize.

Later, fellow Explorer David Gruber invited him to collaborate on his work with sharks, jellies, and turtles after seeing Varma’s talk at National Geographic’s Explorer’s Festival in 2017. By this point, Varma was already sharing with the world about how he zoomed in on bees and parasites to reveal worlds and behavior never seen before by humans.

“He [Gruber] was like ‘are you interested in any of this?’ I grew up wanting to be a marine biologist, so I wanted to do all the things.” But jellies were the low hanging fruit. They could be bred in a basement, they could be FedExed, and that is exactly what Varma did.

It took four years to get the shot. He thought he figured it out, then was met with challenges and went back to the drawing board. He was unknowingly making discoveries about their anatomy and processes for survival along the way–like the fact that they regenerate, which Varma witnessed by accident after several were injured in a plumbing mishap.

“You stumble upon some weird feature or behavior, and you go back to the scientists and they’re like, ‘No, we don’t know what that is. Actually, can you send us more of that video? Because we’ve never seen that before.’”

Something similar happened with the honeybees in 2015, when he unveiled his 21-day life cycle of bees project. After six months of dozens of attempts, and Varma engineering his own incubator and perfecting the conditions for bees in each stage, from larva, to pupa, to honeybee, he captured the development process and unique behavior scientists had not yet seen. “That was the first time I started to see photography and science not as these mutually exclusive things, but as synergistic efforts.”

Challenging assumptions

Though magazine editors advised he shouldn’t worry about the science as a photographer, it was impossible to document biology without understanding it. The photo of a parasite wiggling out of a cricket’s belly, he reminds, is a biological phenomenon immortalized. The conditions had to be duplicated, and therefore, understood. “It can’t just be where you put the light or when you hit the shutter. It has to be that in combination with an understanding, discovery, or an exploration.”

In many ways, Varma feels a sense of duty to help people challenge their assumptions of the natural world. His most gratifying audience to serve are students, because in his words, their minds are still “squishy.”

“The higher challenge is getting someone who is entrenched in their assumptions about the world. How do I resquishify?” He’s as relentless in his pursuit of creating images stunning enough that people will reconsider their opinions about parasites, as he is in documenting hummingbirds, apart from their cuteness, as incredibly complex.

Varma’s work makes the case for how a compelling image can change minds and make room for new ideas. Even the WonderLab is a challenge to traditional thinking.

“When I go to a science lab, to me, it is not a place that inspires curiosity. It’s one step up from an office building.” The WonderLab is an emporium of materials for life-sustaining invention and storytelling, and beyond its functional purpose, a minimalist beauty.

His workshop is stacked top to bottom with hardware and tools. Inventions are sorted by project in blue bins, stacked floor to ceiling on stationary shelves. It’s probably the most industrial-looking part of the lab, and it’s tidily tucked away behind double doors. The process of inventing and engineering, like nature in creation, can be isolating, chaotic, and at times brutal, but necessary before reaching completion.

A few giant, jellyfish-shaped light fixtures hang from the ceiling. Rows of rolling desks are uniformly scattered on the naturally-lit wooden floors, and some of Anand’s most proud work sprawls the walls as giant murals. With a button click the window shades come down and the lab goes dark. “We’ll be able to set up theater nights or movie mode,” he says. The space is designed to accommodate 32 students, and it’s hardly an ordinary classroom.

“For a while we had crabs, mussels, and an urchin in there. Students can make observations with the naked eye, then with the cameras.”

One thing about Varma, he does his research. His model comes from studying the book Slow Looking by Shari Tishman, who designed a framework for fostering curiosity and attention–exactly what Varma was after. “This is my life and my work, she just put a name to it and structure to it, and lessons for how to teach it. I thought, ‘oh this is exactly what I do. How do I pair it with the photography specific focus we have?’”

‘The craziness of science’

At this point, Varma and his two lab assistants, Mark Unger and Jacob Saffarian, receive a shipment. “It looks like a sarcophagus,” one of them comments. The wooden box does fit the bill of something housing remains, but inside is a sump tank–a crucial piece to complete the aquarium in progress. It will house cuttlefish and squid eggs that the team will welcome a few days from now. With guidance from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Varma has learned how to engineer the conditions to keep marine creatures alive.

Varma is a fascinating hang. For someone who spends so much time entrenched in science, technology, and his own art, he’s incredibly good at explaining complex ideas in layman terms.

“The way to think about a jellyfish’s life is more like an apple tree. You have this tree that produces apples, the apples fall and get carried off, but the tree dies. In the case of the jellyfish, after it produces those jellies, it turns back into a polyp (a baby jelly). It’s not done producing. In one species, that polyp can clone itself seven different ways in at least one species.” He saw it first while documenting a jellyfish in his tank that was mowed down by another soft bodied marine animal, a nudibranch, and the jelly left behind a little copy of itself in an armored casing. Some jellies reorganize their bodies into polyps without ever really reproducing. “They call it the immortal jelly.”

“There is no known end of life to that polyp that can clone itself indefinitely.” Could he have documented the next breakthrough for human’s insatiable thirst for immortality? “It could be that it’s never going to work in humans. It could be that it does, who knows. That’s the craziness of science.”

It was always fish

From about eight years old, Varma was decided on becoming a biologist. He toyed with the idea of studying ichthyology, which would allow him to get a unique look at fish. Since the time a channel catfish stuck its nose out at him at the Atlanta farmer’s market when he was just a boy, it was fish that had his attention. “I was just tall enough to peep over the edge of the tank. One of the fish jumped out at me. I remember falling over backwards, stunned by this fish.” It was the beginning of an infatuation. Though, he also remembers asking his parents to hold off on cleaning or fileting a rainbow trout from his high chair, so that he might marvel at all its scales and colors. Every bit, he recalls, “was stimulating and surprising.”

At 14, he got an early work permit to take a job at the aquarium store. He needed to fund his hobby of keeping up fish tanks–seven of them in total–at home.

His senior year of high school he borrowed his father’s digital camera, taking it on trips with friends into the woods and coming back with experimental photos. Shortly after graduation, he took a summer job as a photo assistant to Explorer David Liittschwager on an assignment for National Geographic. His job was to rappel down caves in Sequoia National Park and help Liittschwager photograph species new to science.

Later, he worked on a project in Hawaii, where he collected baby flounder, shrimp, and crabs. It was his job to keep them happy while Liittschwager photographed them. By now, he had spent enough time around freelancers to know the life didn’t appeal to him; he spent years watching people decades into their careers sometimes scramble for work. He was dead set on getting a graduate degree after one last field adventure, but the opportunities kept coming.

“I’m not going to turn down an opportunity to go snorkeling in Tahiti or tree climbing in Costa Rica,” he remembers, laughing. Eventually, he began pursuing his own projects, which included early support from the Society through a Young Explorer Grant, funding his project documenting the wetlands of Patagonia. Fifteen years on, he’s continued carving his own path and welcoming the world into his mind.

Every bit takes time

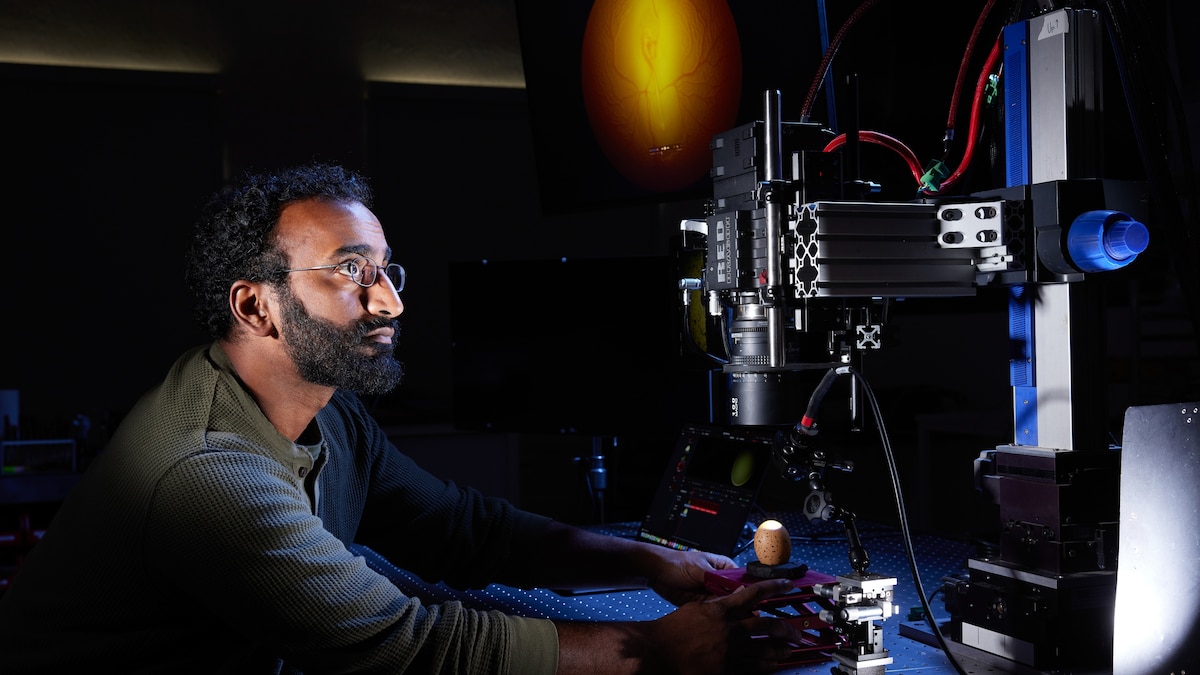

A few feet from the aquarium room in the lab, a couple of chicken embryos are in development. The oldest one at the time of this visit is 14 days into its life in the egg. The future chicks’ participation in Varma’s latest work is the materialization of a childlike fervor he’s maintained since seeing chicken embryos at San Francisco’s Exploratorium. Now, equipped with the tool of his trade, he’s been documenting their life at its earliest stage, from a small clump of cells, to chicken embryo, to hatchling, by going inside the egg.

He calls his method of access “surprisingly simple,” holding up surgical scissors which he uses to cut a harmless window into the shell that allows humans to see life forming as never before. He adopted the method from the lab at the University of California, San Francisco.

The results speak for themselves, but Varma is still refining his system to avoid jagged edges, lopsided holes, and obstruction from intrusive shell dust. “We’re prototyping the way to do it with a dentist drill, essentially. A micro-motor that will allow us to grind a hole in the shell without puncturing the membrane.”

It was trial and error that brought Varma to success with the chicken embryo. The egg, he learned, needs to be rotated every so often–usually the job of the mother hen–to ensure the embryo doesn’t stick to the shell membrane. How do you rock the embryo and still photograph it? This time he outsourced an engineer to develop a system that would rock the egg in its chamber every five minutes, while a camera hanging above it snaps a photo at the precise moment.

Every bit takes time. His quickest turnaround from set up to getting the shot was when he photographed bats. “It was the second try. So it was two or three days. That’s the shortest of any picture I’ve ever taken.” The photo is appreciated in gigantic form in the lab, splashed across one of its main walls, facing a sister print of Varma’s hummingbird work, which he calls his most precious.

The hummingbird project is the culmination of ten years of work. Its video component reveals details about the tiny bird’s biology, only detectable at some 2,000 frames per second in 4k resolution—slow and clear motion. The picture is stunning, and educational. After spending more than eight years working with scientists on how to handle and train hummingbirds, he documented how these creatures deal with rain, dry themselves, and use their forked tongue to feed. It takes a viewer beyond “their colorful cuteness” to reveal a tough flier with impressive biomechanics.

With jellyfish he was starting fresh. He had to spin their housing conditions and photography set from scratch, which took three years of testing aquariums, experimenting with water flow, lighting, and learning how to manage their biology.

There are three streams that need to converge to get the shot: the biology, the engineering and the photography. By his estimation, Varma’s work is 65 percent engineering, 30 percent biology and five percent photography.

“What’s the actual amount of time that the camera is on and recording? That’s probably like point one percent,” he reveals. The most important thing is perfecting the conditions to keep these animals alive, then, determining what phenomenon he aims to capture and what kind of engineering is needed to make that possible. “Then you can start to make aesthetic decisions about how to get the image,” he concludes. But as nature has it, the process can be messy, nonlinear, and even look regressive.

“It never happens in just those three steps. You take the picture and it doesn’t look good. You have to go back to engineering to get the lighting or angles right, or you don’t even see the phenomenon you’re trying to and you go back to the biology. Sometimes you go back to square one.”

Resetting wonder

With the cephalopods on their way to the lab, Anand is very much in the biology phase of his latest lifecycle visualization project, Metamorphosis. He’s not sweating any deadline in particular, he doesn’t know how long it’ll take to get the shot, but Varma is equipped with the experience to know he’ll have to tool and retool again.

To Varma, photography “is just a vehicle for creating a sense of wonder.” His work is proof of a deep understanding of the subject; to have become intimate enough with nature to know how to keep it alive, to be familiar with its quirks, and to show off its most flattering angles.

The squid and octopus eggs are a new photographic, biological, and engineering experiment. How do you keep them clean, aerated, and keep the view clear enough to observe how it’s growing? Does this future squid need to be rotated in its encasing while developing? Maybe there’s something cool to see when it hatches but not while it’s growing–he doesn’t know yet. The childlike fervor Varma still retains for the natural world makes it worth all the work. Certainly, he’ll learn something.

His work is a front row ticket to life up close, and yet, nature still holds secrets, and they can sometimes seem drenched in paradox, Varma says. For example, how a tiny embryo is robust enough to withstand being jostled around, but has an equally delicate alchemy. “All of a sudden at the very end [of development] because at step two of 483 was slightly off, that process gets stopped,” he explains, amazed and puzzled.

“I feel like I’m too early in the process to have any deep insights about the world, but it feels ripe for understanding. I know enough to know this is not going to all fit in a neat box at the end. I have more questions than when I started.”

Growing into his own career identity, at the cornerstone of disciplines, means getting comfortable with not fitting into a single mold. One of the payoffs, though, is that Varma’s dedication to the nature he photographs, on top of an innovative approach to his craft has earned him street cred with scientists, photographers, and engineers alike. “You don’t have to accept what the dictionary definition of a scientist or a photographer is, because there’s magic at the intersection,” he encourages.

He hopes to impart this open-minded approach to career development on the new generation through his mentorship, particularly in the sciences and photography.

“Images serve a higher purpose that I’m still trying to define concisely.” Varma says. “The goal is to create a connection between people and science, and redefine how people relate to nature. I think that’s most powerfully achieved through creating a sense of wonder.” And though humans grow into adults and the threshold for what produces wonder “seems to go up,” he’s compelled to showcase the natural world as new, time and time again. His wheels are turning now.

“What is it going to take to reset that sense of wonder? That feels like what my task is.”

Anand Varma has curated a new book titled Invisible Wonders: Photographs of the Hidden World, featuring work by other National Geographic Explorers, scientists and photographers. The pages guide readers through the eye-popping world of photographic wonders: fascinating images that reveal colors, shapes, and configurations, micro and macro, that cannot be seen with the naked eye. Available Sep 26, 2023.

ABOUT THE WRITER

For the National Geographic Society: Natalie Hutchison is a Digital Content Producer for the Society. She believes authentic storytelling wields power to connect people over the shared human experience. In her free time she turns to her paintbrush to create visual snapshots she hopes will inspire hope and empathy.

[ad_2]