[ad_1]

Perusing Richard Whitehead’s photographs of the night sky, one can be forgiven for mistaking them for professional images captured by the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes. Whitehead’s online astrophotography gallery includes celestial structures more commonly captured by orbiting telescopes and large mountaintop observatories.

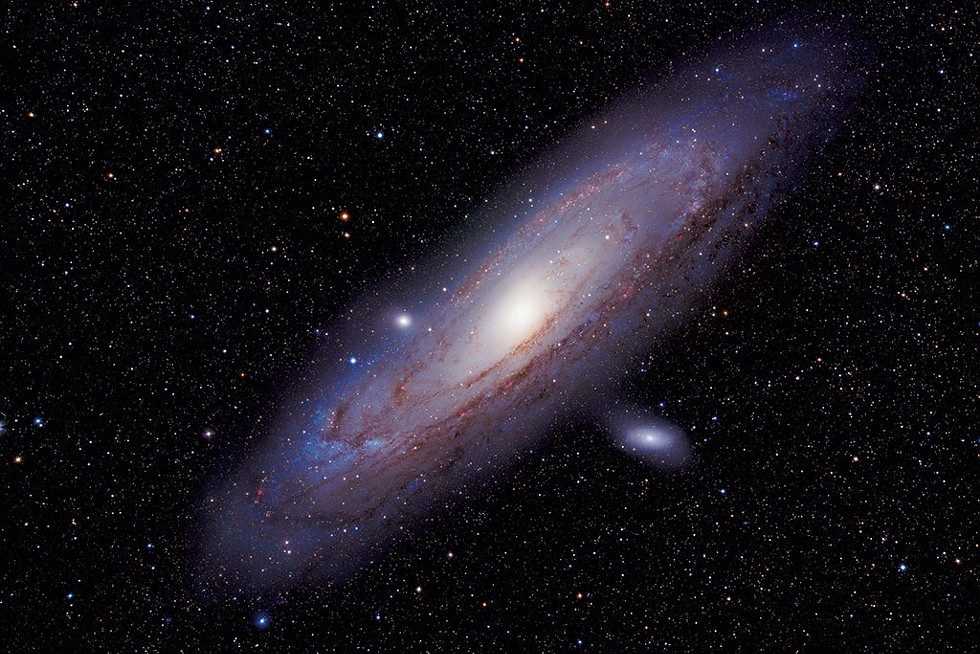

Among them: the zoologically named Horsehead, Tadpole, Pelican and Elephant’s Trunk nebulae; the spirals of the Whirlpool, Pinwheel and Andromeda galaxies; and other cosmic structures that offer clues to the origins of stars and solar systems, including the Wizard, Heart and Soul nebulae.

But all of Whitehead’s amateur photos were shot through comparably small, ground-based telescopes, sometimes in his front yard in St. George, other times in a New Mexico desert. And while Whitehead’s scopes are considerably more sophisticated — and expensive — than the kind children receive as holiday gifts, he noted that many of the heavenly bodies he’s photographed can be seen with a modest investment of time and money.

In fact, Whitehead’s passion for astrophotography is a relatively new hobby that he took up at the start of the pandemic. In just three years, the 61-year-old has become a self-taught expert on space photography, producing stellar images that circulate widely among space enthusiasts and researchers alike. Whitehead often receives professional accolades for his photos, and amateur astrophotographers around the world now contact him for advice.

While Whitehead has a website where he sells his prints emblazoned on hats, mugs and T-shirts, he’s not in it for the money.

“I like to think of myself as a visual artist,” he said. “I like the creative aspect of it, though I’m fascinated by the science, too.”

Whitehead, who runs a Burlington software company that he cofounded 25 years ago, lives alone in St. George with Herschel, his exuberant 6-month-old Australian labradoodle puppy, who resembles a teddy bear you’d win at a county fair. Amid the ample collection of musical instruments in Whitehead’s home — guitars, basses and drums — are framed prints of his space photography.

Many of those prints are quite large. They include one of Whitehead’s best photos to date: a stunningly vivid, 3-by-4-foot shot of the Jellyfish Nebula, captured in St. George during four virtually crystal clear nights. Last month, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration chose the image as its “Astronomy Picture of the Day” and posted it to its Facebook page — considered high praise among amateur astrophotographers.

Another image of Whitehead’s, of the Siamese Twins galaxies, was similarly recognized by the Italian astronomical society Gruppo Astrofili Galileo Galilei. Still other images have received accolades from the Amateur Astronomy Photo of the Day website, which receives thousands of submissions annually from photographers worldwide. Though few people get theirs posted, Whitehead has already had four of his photos featured on the site.

Astrophotography is more complicated than terrestrial photography and involves layering multiple frames to produce the final image. Whereas conventional photography typically entails shutter speeds of tenths, hundredths or thousandths of a second, astrophotography involves stacking dozens of images, each created using 20- to 30-minute exposures, often shot over multiple nights.

Once Whitehead has gathered all that raw digital data, he processes it using various software, including Adobe Photoshop and PixInsight. The latter is an astrophotography program that aligns the stars in the overlapping images and eliminates unwanted “noise” created by thermal and atmospheric disturbances.

Whitehead has five telescopes. Usually, though, he shoots his Vermont-based images through a 106-millimeter (just over four inches) refractor scope mounted on a tripod on his front lawn. A refractor scope has a long optical tube with a convex glass lens at one end. Light from the sky enters through that lens, then exits through the eyepiece or camera shutter. (Whitehead does all of his viewing on a computer.)

In all, his Vermont-based kit, including the telescope, tripod, filters, motor, camera and computer link, cost him about $50,000. While he acknowledged that’s a lot of money, he added, “When I think I’m ridiculous, I look at the guy who spent half a million.”

Whitehead also rents space at a professional telescope hosting facility in a New Mexico desert. “They get about 300 clear nights a year, as opposed to Vermont, which gets about 20,” he said. “It can be good here, but it’s very hit or miss.” In New Mexico, he houses his reflecting telescope, which uses curved mirrors rather than lenses to capture and focus the light. Like Whitehead’s Vermont-based scope, he controls the reflector scope in New Mexico remotely via a laptop in Vermont.

Whitehead had no formal education in astronomy or astrophysics, but he grew up surrounded by high-tech gadgetry. He was born and raised in England, in a small rural town in the East Midlands. Whitehead’s father, a decorated military radio operator during World War II, ran a maritime radio station and was also a ham radio enthusiast.

“There were always wires and equipment around the house, which is a bit like me,” he said. “So I guess I inherited that.”

As a child, Whitehead had a small backyard telescope for stargazing, and his small rural hometown of about 5,000 people had very little light pollution. Whitehead was also a fan of Sir Patrick Moore, the famous British astronomer who for years had a BBC television show called “The Sky at Night.” Whitehead described him as a 1960s version of Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Whitehead attended university, where he received a degree in radiography, then spent three years working as a medical X-ray technician. Feeling limited by the job, he changed careers to sales and marketing for the pharmaceutical industry. Then, in the late 1990s, he cofounded an analytical software firm called CSL Software Solutions. With clients in the Northeast, and having enjoyed several previous visits to Vermont, Whitehead moved the company to Burlington in 2006.

Already an avid amateur photographer, Whitehead had a small telescope that he used only rarely for stargazing prior to 2020. When the pandemic hit, he started playing around with the telescope again, then bought himself a small star tracker that follows the movement of celestial objects across the night sky.

Bored one night during the lockdown, Whitehead aimed his telescope toward the Orion Nebula and shot some photos using 30-second to one-minute exposures. Though his first one was “a rubbish image,” Whitehead said, its colors inspired him to create better ones.

“And that was the start of the addiction,” he added.

Soon, Whitehead upgraded to an 11-inch reflector scope, which enabled him to shoot much sharper images of galaxies and nebulae. (He’s less interested in photographing planets but has some good images of the moon and comets.) Much of the processing software Whitehead needed was available online for free. Numerous catalogs for locating and identifying celestial objects are also available online. Whitehead integrated his expertise in databases, which he acquired as a software developer, into his newfound pastime.

How does artistry enter the cosmic picture? As Whitehead explained, some of the creativity is similar to that of conventional photography: framing the subject, deciding on the picture’s depth of field, and choosing the right shutter speeds and filters. Whitehead uses very narrow filters — a mere three nanometers wide — that enable his telescope to peer through clouds of dust in space.

In astrophotography, Whitehead explained, the photographer also has the ability to change the colors that appear in the final image. The so-called “Hubble Palette,” made famous by the Hubble Space Telescope, is merely a convention that NASA developed: blues represent the presence of oxygen, oranges and reds the presence of hydrogen, yellows for sulfur, and so on for other elements. However, as Whitehead pointed out, amateur astrophotographers can choose completely different colors to represent those elements, rendering familiar objects in space in new ways.

Not all of Whitehead’s subjects have been photographed countless times before. He spent 30 hours photographing the Bear Claw Nebula, of which, he said, there’s only a handful of other images online, and “none of them particularly great.

“Scientific images aren’t necessarily pretty images,” he added.

Naturally, when photographing objects millions of light-years away, astrophotographers still encounter obstacles in their own neighborhood, from heavy cloud cover and light pollution to the proliferation of satellites, such as Starlink, which are highly reflective. While Whitehead can use software to eliminate some of the trails and reflections created by passing aircraft, satellites and meteors, often he has to throw away those images and take new ones.

Not all unexpected images are unwanted. In Whitehead’s Jellyfish Nebula, for example, he captured something he didn’t expect and couldn’t identify, which may be a planetary nebula, a region of cosmic dust and gas created by a dying star. And in 2021, while photographing Messier 78, a nebula in the constellation Orion, Whitehead caught Herbig-Haro objects, which form when gas ejected by young stars collides with clouds of other gas and dust at high speeds. In his photo, they appear as narrow red jets.

While Whitehead’s images have caught the attention of some professional astronomers and researchers, most of his fans are amateur space enthusiasts like himself, who enjoy pondering the vastness of the universe and our place in it.

“Whatever’s going on in the world,” he said, “you can look up at the sky and realize how small and insignificant we are.”

[ad_2]