April 7, 2022

Three photographers discuss the art and craft of intimate spring photography, and how to make your images stand out from the rest, with Claire Gillo

Now that Spring is upon us, why not try getting creative with your landscape and nature photography? Photographers Charlotte Gibb, Mark Gilligan and Jo Stephen share their tips for intimate spring landscape photography below.

Charlotte Gibb

Charlotte is a California-based landscape/nature photographer and educator. See www.charlottegibbblog.com, on Facebook @charlottegibbphotography and Instagram @charlottegibb. She is the author of Get Intimate: Making A Personal Statement with Intimate Landscapes and is exhibiting at the Ansel Adams Gallery, Yosemite National Park, from 23 April until 3 June this year.

‘Intimate landscapes are compositions that have been derived from the larger scene,’ says US photographer Charlotte Gibb. ‘It could be a photograph of a small section of beach, or a group of trees, or it could be a photograph of a section of an entire mountain.

‘Typically, the sky is not part of the composition, so intimate landscapes don’t rely on attention-grabbing sunsets. They are more subtle, and, for me, often have an element of symbolism in them,’ she continues. ‘It can be a challenge. Intimate landscapes can’t rely on grand, colourful scenes to inspire awe in the viewer, so the photographer has to be more clever about how to compose. Don’t feel dispirited if your photographs aren’t compelling when you start. Just keep at it.’

View of Yosemite Falls from a hotel room. Taken with a very long focal length of 560mm

Canon EOS R, 100-400mm + 1.4x III extender, 1/80sec at f/16, ISO 400. Image: Charlotte Gibb

Rather than hunting for subjects, Charlotte studies a scene for design elements. ‘What shapes do I see?’ she says. ‘Pine trees are triangle shapes. Deciduous trees in winter are a series of lines. I look for repeating patterns, or contrasting colours. I also look for interesting light.’

Charlotte’s stamping ground is California. It’s home to a wide variety of landscapes, from rugged coastlines to ancient Redwood trees and deserts. ‘My heart-of-hearts is with the Sierra Nevada mountains and Yosemite National Park, though,’ she says. ‘There is tremendous diversity, and as much as I go back again and again, I always come away with a new composition. My most meaningful work has come from these places.’

Taking precautions

When asked how she keeps herself safe in this environment Charlotte replies, ‘Good question! Yosemite wildlife isn’t really dangerous unless you look for trouble. Sure, we have black bears, but they are more interested in your sandwich than in you. We do have mountain lions, and like bears, they can be dangerous if they have cubs nearby, but otherwise they are reclusive. I have never seen one in the wild, though. ‘The biggest danger in Yosemite is one’s own recklessness.

Although she has photographed rainbows on Yosemite Falls many times, this was the first time Charlotte witnessed two of them. Canon EOS R5, 70-200mm at 92mm, 1/100sec at f/13, ISO 400. Image: Charlotte Gibb

I also carry a Spot GPS device. It allows my husband to keep track of where I am, and would also let me call in the helicopters if I were to find myself in a critical situation. Fortunately, that has never happened.’

Charlotte has two Canon EOS R5 bodies and a variety of Canon RF lenses. ‘But my favourite lens is my Canon RF 70-200mm f/2.8 L IS USM – it’s my precious!’ she jokes. ‘It has the perfect range of focal lengths for the type of photography I do. Long lenses are great for creating atmosphere and zeroing in on smaller sections of the landscape.

I also love my Arca-Swiss d4 Tripod Head with a Classic Knob (Geared). It allows me to make minute adjustments when composing.’ When it comes to composition, Charlotte likes to stay spontaneous. ‘The feeling of connection with nature is key. I internalise what is around me.’

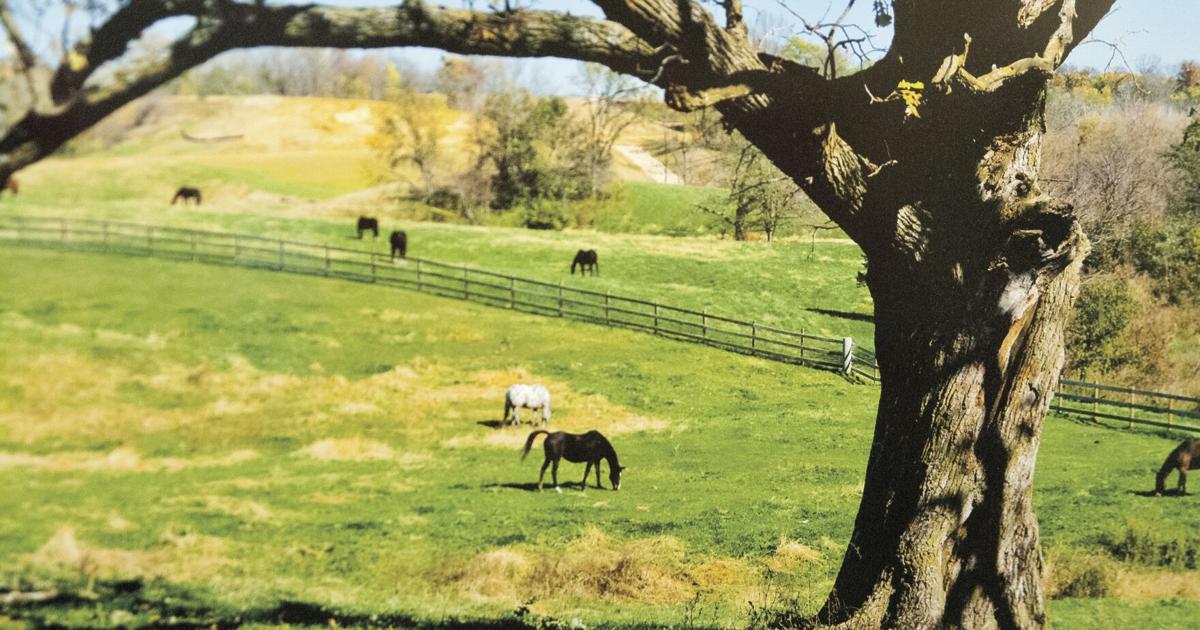

Dogwoods in bloom in abundance in Yosemite Valley in the spring, but congregate in just a few places. This scene was spotted near the east end of the valley Canon EOS 5D Mark II, 24-105mm at 105mm, 2.5secs at f/16, ISO 100. Image: Charlotte Gibb

Charlotte’s top tips for intimate spring landscapes

- Slow down. Find solitude. Connect with nature. Explore. Be curious.

- Zoom in. Either use a longer lens, or zoom with your feet. Getting up close will help to eliminate distracting elements in the scene and simplify the composition.

- Eliminate the sky. The sky is usually the brightest part of the picture and will draw the eye away from your subject like a magnet.

Mark Gilligan

Mark has been a professional photographer for more than 40 years. He is a LEE Filters Master, a winner of the #OMGB in LPOTY, and runs workshops in the Lake District and Snowdonia. Find out more at www.wastwaterphotography.co.uk and follow on social media @wastwater1

Mark Gilligan enjoys hunting for less obvious landscapes. ‘As well as larger, grander, landscapes, I also derive pleasure in finding images that aren’t so obvious. These could be very close. Some are smaller views or segments of the view that you decide to isolate.’

Make use of empty space in your compositions to create a feeling of calm and tranquillity 1/30sec at f/3.2, ISO 200. Image: Mark Gilligan

In his kit bag, Mark has a Fujifilm X-Pro2 and to shoot his close-up landscapes switches between his Fujifilm XF 16-55mm f/2.8 and Fujifilm XF 55-140mm f/2.8 lenses. ‘The 16-55mm is my go-to lens, though,’ he says. ‘I often shoot using a shallow depth of field which works well with the longer zoom.’ Occasionally, he will hand-hold his camera, but most of the time uses his Gitzo tripod.

Mark loves the spring light. ‘The light begins to get harder, which I find works well with the water-based images,’ he says. ‘I like to retain the detail and “over cook” the surroundings to the limit, thus enabling me to get the image I want. I hardly do anything in post.’

Look for plain backgrounds to frame a plant or flower in the environment. Fujifilm X-T1, 18-55mm at 55mm, 1/2000sec at f/4, ISO 400. Image: Mark Gilligan

Seeking the right subject

To find the perfect subject for his intimate landscapes, Mark will scan the scene to find elements of interest, and doesn’t like to restrict himself. ‘If I see something and it appeals, I will try my best to photograph it and do it justice,’ he says. ‘I like that old word “serendipity”. I’ll happen upon it and if I like it, I’ll take it.

‘A forest can be a good location, but being by the waterside has produced many great images for me – I particularly like photographing reeds. They are usually at their best in the spring and summer, and hard light allows me to overexpose the water, which retains the detail in the plants. Sometimes I can isolate them but a “gaggle” of them can produce interesting abstracts and be just as appealing.’

Mark also finds quarry rock to be good in damp conditions. ‘Wet slate can produce some outstanding colours and potential images.’ To edit his images, Mark uses Lightroom. ‘As I shoot in raw, I make a couple of tweaks, but I use the spot meter on my camera (I know I am old school) and my LEE filters so my exposures are usually very accurate. In short, I can generally deliver an image in under a minute.’ Mark prefers to spend his days outside shooting, rather than sat for hours inside at the computer.

By blurring the backdrop and isolating an individual plant, Mark has created this effective result

Fujifilm X-Pro2, 50-140mm at 140mm, 1/1250sec at f/4, ISO 100,. Image: Mark Gilligan

While traditional in his approach, he also pushes the boundaries. ‘Once I see a subject, I may take it faithfully or create the final result in camera by controlling the light,’ he says. ‘Intimate landscape means different things to many people. It is the one area of my photography where I am happy to experiment and not faithfully photograph what I see, because I am after something different. In order to do this, you need to understand what you are doing with your camera, so make an effort to learn how to control it.’

Mark’s top tips for intimate spring landscapes

- Scope where you are. Not just for that day but for the future. Some things will be obvious, but take your time and look.

- Never be downhearted; if it doesn’t always work – at least try!

- Experiment and don’t be afraid to push the boundaries.

Use the harsher light conditions of spring to your advantage to get results like Mark’s shot of leaves and reeds Fujifilm X-Pro2, 50-140mm at 140mm, 1/500sec at f/4, ISO 200. Image: Mark Gilligan

Jo Stephen

Jo is a naturalist and environmentalist, and has been taking photographs in her local landscape for many years. She also works in nature conservation. Her photography explores her connection to the natural world and her place within it, and is created ethically with a minimal carbon and ecological footprint. Find out more at www.jostephen.photography, and follow on social media @joannunaki

Go in close to find a whole other world of flowers and species. Sony A58, 90mm, f/2.8 at 1/2500sec, ISO 100. Image: Jo Stephen

Spring has always been Jo Stephen’s favourite season. ‘I live in a village surrounded by woodlands carpeted in bluebells and wild garlic in the spring. Watching the landscape transform so dynamically in the spring inspires a lot of my work.’

Jo shoots on her old yet reliable Sony A58 and Olympus OM-D E-M10 III. ‘As much as I’d love a more capable camera, particularly one with in-camera multiple exposure, as an environmentalist I’m happy to continue using these,’ she says. ‘I shoot nearly everything with my macro lens, even landscapes. Spring is a wonderful time for more creative techniques, such as intentional camera movement and multiple exposure. Using movement when shooting is an effective way of communicating the dynamism of the season.’

To find the perfect subject, Jo likes to give herself freedom to experiment, and to explore colours, textures and forms that resonate in the landscape. ‘Don’t worry what anyone else is shooting and don’t get fixated on what kit you have – you can take great images on cheap cameras.’

Using layers of images, Jo has created this striking image of a pink cherry tree Sony A58, 90mm, f/2.8, ISO 100. Image: Jo Stephen

She continues, ‘Shooting up close opens myriad tiny worlds, so if like me you only shoot what’s on your doorstep, it’s still going to take several lifetimes to get bored with the vistas. It should be about the joy of creating, and that means sometimes you’ll come back with awful results, but that’s how you learn and evolve.’

To create her abstracts, Jo uses a couple of techniques. ‘Much of my work involves intentional camera movement (ICM) to varying degrees,’ she explains. ‘It may be that I take a few blurry shots to use as textures with static shots, or ICM may be the focus of the image I’m creating, as in the bluebell shot.

I like to use subtle movement and will pause during the motion to let elements of the composition “stick” and remain in focus. I look for texture and light in the composition; any highlights will become streaks and lines throughout the image, so you need to think about how you will use those if you start moving the camera erratically. It can be hit and miss whether the light will create interesting or jarring shapes. I like to make use of contrast, and often look for light subjects against a darker or boldly coloured background.’

This image was created with a forward circular movement, using half the exposure time to rest upon the bluebells and the remaining half to move the camera. Sony A58, 90mm, f/20, ISO 100. Image: Jo Stephen

Multiple exposures

Jo also likes to layer her images using multiple exposures. ‘As I only have an old entry-level camera, I am unable to do this in camera, so this work is made in post. I’ll collect a few images, both ICM and static, and maybe a few that are completely out of focus, to add colour and texture. After a while you get an idea of what you need to shoot to create the images you have in your mind later at the computer.’

When it comes to taking intimate landscapes, for Jo the joy is not so much in the final result but rather the act of being in nature.

‘Shoot what you love – for me that’s my walks in the woods and meadows. I think if you care about your subject, then you’ll connect with it and find a way to express that connection. For me, photography is about the process, not the resulting image.’ She continues with a word of warning. ‘Any nature photographer needs to be mindful of their subject. Basic field skills will help you to get closer to nature and understand the behaviours of the wildlife you’re watching.

But, more importantly is the need not to disturb or impact in any way on those natural behaviours. For this reason I won’t share locations of rare species and don’t geotag.’ Jo recommends any nature photographer to have a look at the RPS Nature Photographers’ Code of Practice, which outlines best practice for ethical nature photography.

Cherry blossom lends itself perfectly to creative photography. Image: Jo Stephens

Jo’s top tips for intimate spring landscapes

- Visit the woods in the early morning or evening, as the light provides that beautiful contrast.

- Shoot into the light with a wide aperture for airy, romantic images.

- Look for pattern or contrast in the landscape (intimate or wide), as this makes for great ICM imagery.

This abstract spring image of wood anemones was made using ICM and multiple exposures. Sony A58, 90mm, f/13, ISO 100. Image: Jo Stephen

View more tips for Spring photography here: 33 Essential Spring Photo Tips

Further reading:

The world’s best nature photographs of 2021 revealed

Best lenses for wildlife and nature photography

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you’ve submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.