[ad_1]

Installation of “Portlanders: Nick Gervin” at Portland gallery 82Parris. Photo by Nick Gervin

Two shows in Portland address worlds and phenomena we often tend to miss. “Portlanders: Nick Gervin” at 82Parris (through June 23) presents a largely invisible Portland, at least for those of us without active night orbits or curiosity in exploring the city’s underbelly (figuratively and literally). “The Flower/The Soil” at Notch8 (through July 8) taps into the essences of nature, specifically the more subtle realms of its inner life.

Nick Gervin is one of Maine’s most captivating and idiosyncratic photographers. His show at 82Parris (formerly New Systems and now, as before, run by another handful of young artists) illustrates why. After two traumatic head injuries, a diagnosis of post-concussion syndrome, depression, poverty and addiction, Gervin developed a hypersensitivity to light and noise, forcing him to rove his native Portland with a camera in the dark and quiet of night.

The process, he acknowledges, was essential to his recovery, but also a way of capturing and rediscovering the place of his birth in all its richness – not just the scenic lighthouses and lovely neighborhoods, but grittier areas of the city and marginalized populations that are part of the fabric of neighborhoods, yet not often deemed worthy of artistic (or other) representation.

Did this predilection toward a specific visual perspective form from his multiple traumas? It’s an interesting question, but I tend to think he’s always possessed an eccentric – and in a way, more humanely open – view of life, capturing scenes and situations few others afford even a cursory glance. The most interesting images leave us perplexed and, perhaps in their ambiguity and non-judgmental observation, even a little uncomfortable. “What on earth is going on?” our minds demand to know, or “What just happened here?”

Nick Gervin, “Plate #27” Photo courtesy of the artist

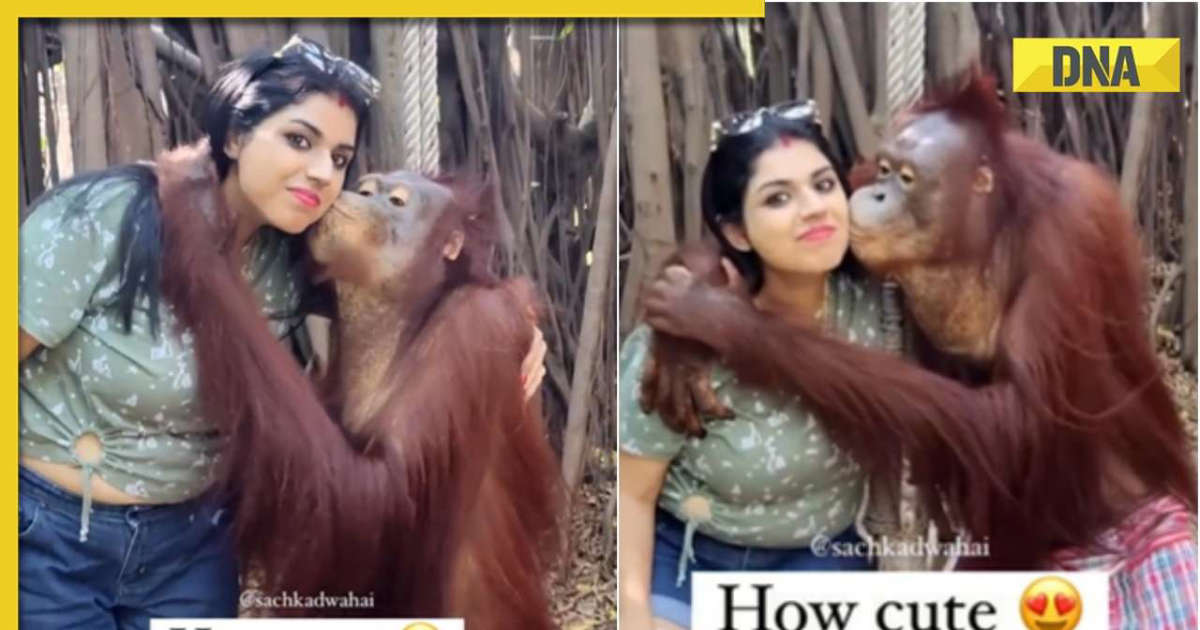

Gervin can be quite funny, as in one scene of a couple seen from behind as they exit a performance space, the audience guffawing, covering their gaping mouths in mild shock or merely bemused.

He appreciates the spontaneously sardonic and witty, as in a barbershop window he crops cleverly to include an American flag with only part of a slogan above it: “Land of.” We suspect the rest reads something like “the Free and the Brave.” Instead, Gervin spied the partial reflection below the slogan of the word “service” from a shop across the street. Compositionally, the intended patriotic message now reads “Land of vice.”

Or there’s the photo of a shirtless, heavily tattooed man on a bicycle, another bike slung over his shoulder. It seems obvious the guy’s just stole the second set of wheels, yet behind him on the sidewalk, two policemen don’t even notice as they casually shoot the breeze.

Often images can be slightly creepily squeamish (an unseen person’s hands filling a syringe with newly cooked heroine) or unnervingly enigmatic, such as yellow police tape marking off the Congress Street Starbucks while a man loads a body bag into a hearse parked in front of it. Did someone suffer a heart attack while ordering their latte, or did someone expire on the street? Did a sidewalk murder just occur?

Nick Gervin, “Plate #04” Photo courtesy of the artist

Gervin also prowls the city’s subterranean tunnels. His shot of a man’s legs dangling from a manhole cover as he enters or leaves a tunnel, is enlarged here to wall size. It’s nice to see these prints in bigger scale – many of which I’ve seen developed in smaller format at The Bakery Photo Collective, where he is executive director, or in his beautifully bound book, “Portlanders,” on sale at 82Parris or through his website.

It’s also great to witness Gervin working in video. A dark curtained room projects a scene shot in a tunnel while we hear traffic rushing overhead and water trickling and flowing inside the tunnel. It’s the essence of his work: capturing the existence of things most of us completely miss.

FERTILE EARTH

“The Flower/The Soil” is a mixed bag in terms of media, genre and style. Basically, six artists – Tanner Wilson, Nate Frost, P Guilmoth, Erin Bassett, Chel and Brian Doody – were asked to respond to the subject of the title. The unquestionable standout here is central Maine-based Guilmoth, whose work buzzes with primal life and feels infused with the natural poetry of the earth. They work, in fact, with actual soil, as well as pine-tar smoke, spider webs clipped from their moorings and applied to paper, ash, stones, coffee, photography, oil paint, charcoal and other materials.

P Guilmoth, “Smoke & Powdered Milk 2023” Photo by Bret Woodard

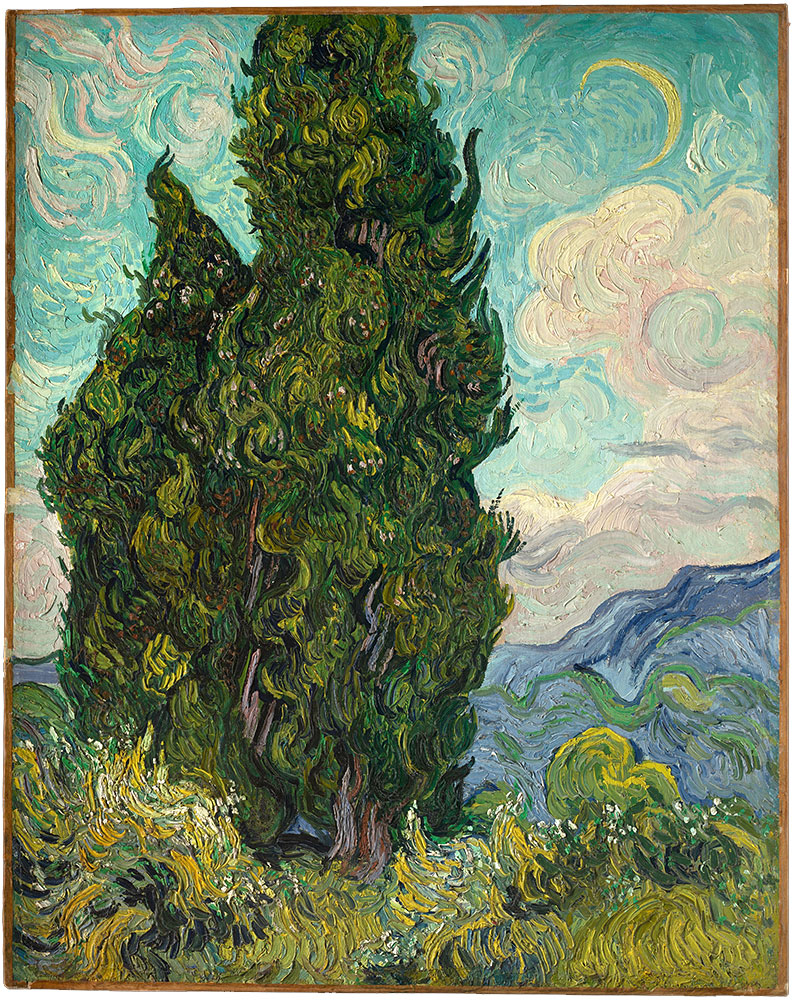

Guilmoth is worth a review unto themself. Suffice it to say that their most easily grasped piece here practically book-matches two spiderwebs into an unusual sunburst shape, one colored white with milk powder and mounted on black cardboard, the other tinted black with pine-tar smoke and mounted onto what looks like an old photo cardstock. It’s a lyrical meditation on the delicacy of existence, the effects of multifarious phenomena on our lives, our sense of home and place, subtle essences we rarely apprehend beneath the surface of things, and the miracles of nature.

Guilmoth also offers a large-scale photograph that literally captures the ephemerality of a moment. To achieve it, they asked friends to stand on a dirt road, throw handfuls of dirt and flower into the air and quickly get out of the frame. The resulting image looks like specters walking toward us on the road while also freezing an event in memory. This artist touches into profound eternal questions through the materials of our ecology.

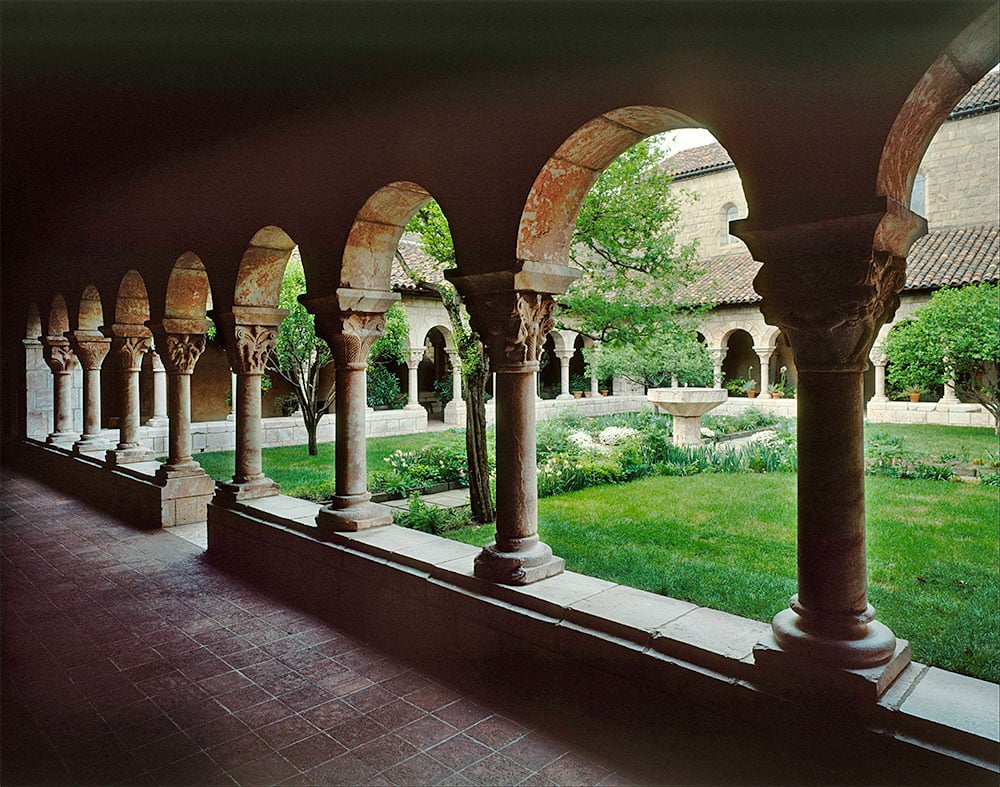

The paintings of Portlander Chel, which limn the line between abstraction and representation, occupy the opposite end of the spectrum. Their work is boldy colorful and flamboyantly gestural. Paintings like “I God in the River” appear at first completely abstract. But the closer we look, the more we perceive the body of water, as well as the craggy rock formations bordering it.

Chel, “I God In The River” Photo by Bret Woodard

The title, of course, implies the deeper phenomenological reality of the river, which according to many wisdom traditions has – like all things – an inner spirit. Wisely, gallery owner Sharon Dennehy has placed Chel’s paintings on the opposite wall from Guilmoth’s works, as their polychromatic glory and jagged energy might have disturbed the meditative stillness of Guilmoth’s organic earthiness.

Atlanta artist Wilson, who co-curated the show, presents nature controlled. His highly graphic, black-outlined images are of potted flowers in decorative cachepots. They are easy on the eye, though one senses a struggle between wildness and the human desire to contain it (i.e.: a snake decoration writhing across the surface of a pot containing a cultivated blossom).

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: [email protected]

« Previous

Related Stories

[ad_2]

![Photographer Andrew Smith says: ‘I have been capturing the environment I find myself in by drone commercially and as a personal pursuit for the past five years. In that time that natural world and our relationship with it has fascinated me. [Pictured is] Traprain Law, East Lothian. Once home to the Votadini tribe who ruled this area of Scotland at the time of Roman occupation, two layers of fortifications can be seen at the edges and a huge hoard of Roman silver was found here. Yet despite its rich history and cultural importance, this volcanic plug was mined until it was banned in the 1960s, causing the eyesore you see here.’ (Picture: Andrew Smith)](http://img-s-msn-com.akamaized.net/tenant/amp/entityid/AA1cmV7A.img?h=236&w=300&m=6&q=60&o=f&l=f)

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you’ve submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.