[ad_1]

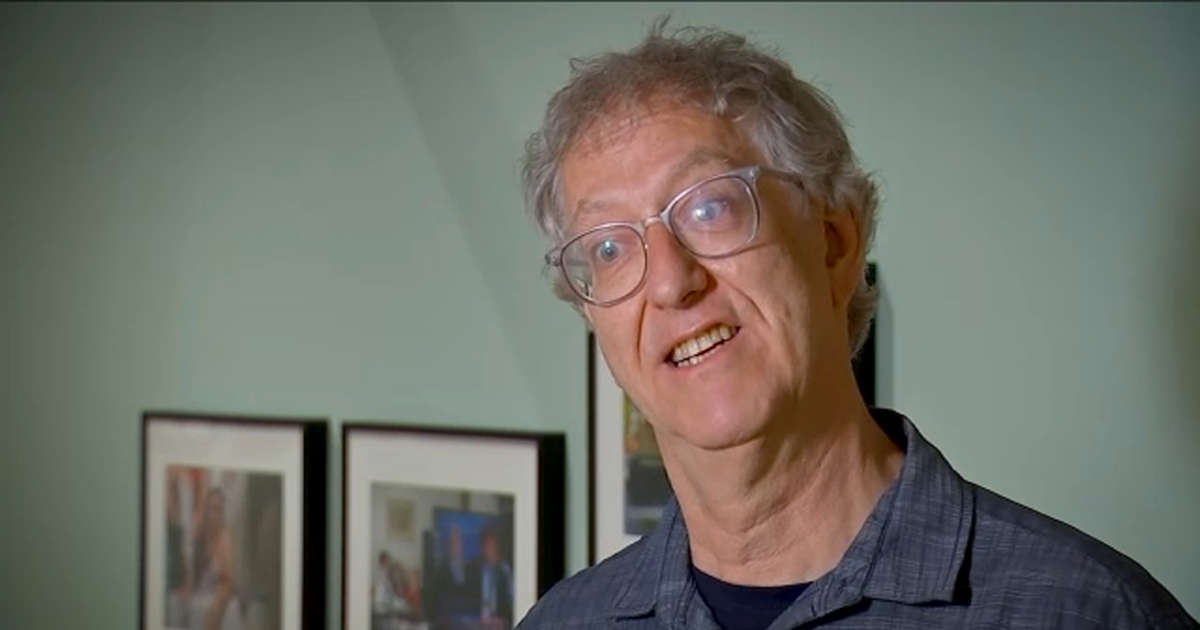

Colorado nature photographer and environmentalist John Fielder sat on a couch inside his Summit County home recently gazing at jagged Gore Range mountains, not through the frame of a camera but a window — a spectacular scene among thousands that he has immortalized.

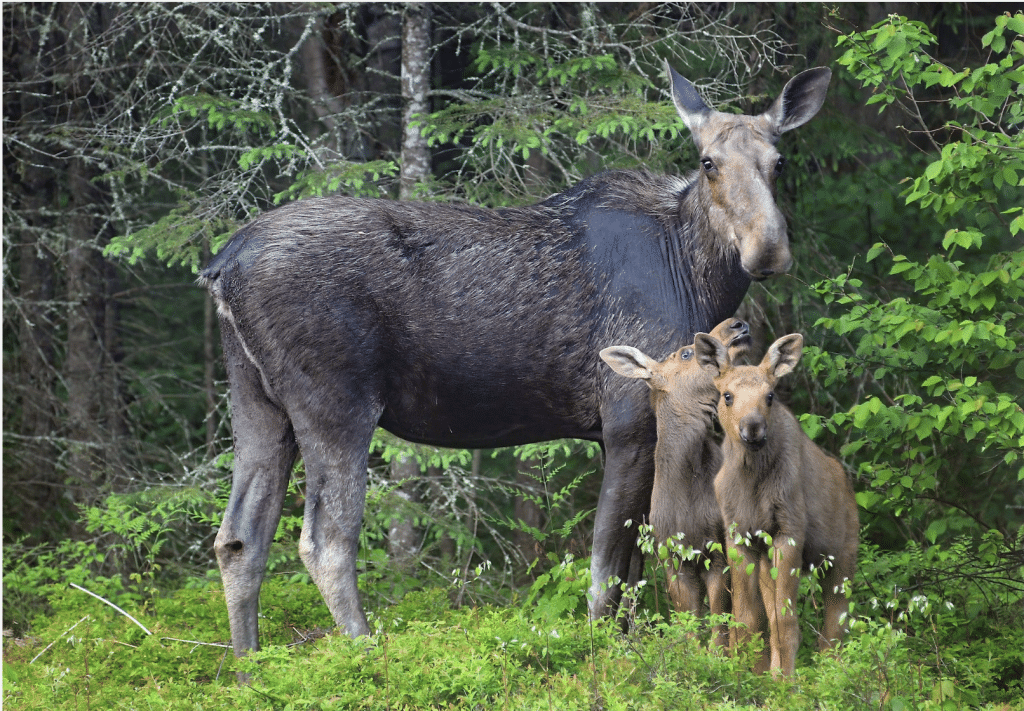

A herd of elk had passed outside. A mountain grouse had been singing sonorously at the door.

“Here I am at 72,” Fielder said, “and cancer is trying to take my life.”

He’s been enduring this pancreatic cancer by relying on the same rational approach he honed in handling countless “curveballs” nature hurled while he covered all of Colorado’s 104,094 square miles photographing landscapes. Vehicle breakdowns above timberline, rafts flipping in whitewater rapids dumping him and all his gear, bears bulling into his camp, sudden storms plunging temperatures below freezing — all became challenges for the father of three to overcome by using brainpower, avoiding panic, and summoning strength the way a mountain climber does in ascent.

Fielder also got through personal tragedies — losing his wife, Gigi, after she was diagnosed at 52 with Alzheimer’s disease. He suffered especially after his son died by suicide.

“You know, I have had to self-rescue myself, get out of difficult situations, over 100 times before,” Fielder said. “To me, this is simply self-rescue number 101. It is a problem to be solved.”

Chemotherapy interrupts a slower existence he’d envisioned, skiing with titanium-reinforced knees, hiking and taking photos in Colorado’s Blue River Valley. But the cancer, diagnosed a year ago, also has spurred Fielder to review his life’s work and focus on his mission: helping Coloradans respect nature, most urgently by slowing global warming and stopping environmental destruction.

Taken together, his photos over nearly 50 years give residents an unprecedented perspective on their natural heritage and how large-scale settlement has affected landscapes where the previous human inhabitants, native tribes, lived sustainably on the land. The photos — including 7,300 entrusted to the public at the state’s History Colorado repository — have become the main visual baseline for assessing changes as the climate warms.

“No matter what happens to me in the next six months, my photos are there at History Colorado,” he said as he sat. “Whatever we can do to stave off the impacts of climate warming, maybe my photos can be part of that.”

Fielder grew up in North Carolina, nudged toward a life in commerce. His father excelled in that arena, building up the Ivey’s department store chain and embracing public service. Upon graduation from Duke University, Fielder fell into work as a real estate broker and, married in 1982 with two children and a third on the way, was managing a May D & F store in south metro Denver.

He and Gigi made an escape plan for a life lived largely outdoors. He would turn his nature photography hobby into a business by selling photo calendars and coffee table books. Forty years later, he tallies some 50 collections of photos he has published with roughly 1 million copies sold.

One book — “Colorado: 1870 to 2000” — leverages 19th-century photos by William Henry Jackson, who was sent by the U.S. Geological Survey to document western territories at a time when census records show Colorado had 39,864 residents. Fielder re-photographed what Jackson saw and created a side-by-side comparison at the start of the 21st century — when Colorado had 4.3 million residents and industries including cattle ranching; mining of gravel, gold, coal, gas, and oil; house-building; and tourism. He dedicated the book to the people of Colorado, urging them to “examine our relationship with the land,” declaring “there is no more beautiful place on Earth than Colorado” and “very few places more fragile.”

His photos of high mountains and valleys exposed Colorado to the world, drawing tens of thousands of visitors and new residents and inspiring some to value the wildness that remained in the West. Perhaps only John Denver, with his song “Rocky Mountain High,” drew more attention to Colorado, said Jerry Mallet, a former Chaffee County commissioner who runs the river protection organization Colorado Headwaters.

Looking back, Fielder wrestles with his role. “Obviously, too many people in one place, too many footprints, can destroy the very place you want to protect,” he said. “But the more people that go out and smell, taste, touch, hear, as well as see, Colorado, the more people are likely to vote for the right candidates and issues on their ballots — to not only repair environmental damage but to protect these areas.”

In the early 1990s, he decided he had to do more to save the natural landscapes he photographed. An environmental movement in the state gained momentum under Fielder’s leadership, Mallet said.

Fielder observed a widening degradation from multiple threats: development devouring open space, tourists overrunning national parks, and now the ruinous fires, droughts, and extreme storms driven by climate warming.

His advocacy began as Senator Tim Wirth was leading work under the nation’s 1964 Wilderness Act to save land in Colorado that was “untrammeled by man” and “retaining its primeval character.” Fielder went out and photographed pristine terrain for a book circulated to county commissioners, mayors, chambers of commerce, and others whose support was required for the federal government to designate wilderness.

Now retired, Wirth credits Fielder as “an integral part of the effort” that set aside more than 600,000 acres of Colorado as wilderness. Fielder “is a wonderful enthusiast and advocate, and his photos surely helped to persuade many Coloradans to support our work,” Wirth said.

Former Congressman David Skaggs, who carried the Colorado Wilderness Act of 1993 to final passage, said Fielder’s photos “served to convey something spiritual about the wilderness” that may have “seeped into the pores of some of our skeptical colleagues.”

Fielder also lobbied for land preservation through Great Outdoors Colorado, the program voters launched in 1992 directing the use of Colorado Lottery revenues to protect wildlife habitat and river corridors and to improve parks and trails. And as Colorado’s population exploded, reaching 5.87 million this year, he supported environmental projects, such as efforts to ensure sufficient water in the upper Colorado, Yampa, and Dolores rivers and protect the canyons they carve as new wilderness.

“He’s one of the most consequential conservationists in Colorado history,” said Save the Colorado River Director Gary Wocker, a longtime friend. Fielder has focused on “art and beauty. … a side of things that humans value,” Wockner said. “He knew that, by taking these beautiful photos and selling them, he was probably leading more people to visit the places. But he wasn’t just commodifying them. He has dedicated his life to protecting those places — and restoring them.”

Damage over four decades of population growth and urbanization in Colorado could have been worse, Fielder said, lauding voters who sometimes made saving nature a priority. “We have accomplished much in the past 23 years to deflect inappropriate development.”

But he has seen a transformation.

“Back in the 1980s, there just weren’t as many folks hiking and camping for the sake of just getting away from the city to enjoy the sounds, smells, taste, and touch — the sensuousness of nature.” Crowded conditions inside costly Front Range cities increasingly drive more people out. “People follow other people to the same places they read about online.”

Climate warming with temperatures rising nearly twice as fast as the global average in western Colorado is shrinking snow and favoring droughts, ruinous fires, and insect infestations — ravaging forests where he used to shoot photos. “Just about all of our Colorado forests between 10,000 feet and 12,000 feet in elevation now are dead, not to mention 5 million acres of dead lodgepole pine forest at lower elevations. I can no longer make a beautiful photograph of green trees in the foreground of a Rocky Mountain composition. And most of the snow and ice that were remnants of ancient glaciers has melted. I can no longer include in my designs the dramatic contrast of a white glacier nestled in a rocky cirque,” he said.

“As an artist, I am not sure I can deal with that.”

In the future, more people likely will move to western Colorado, requiring the preservation of more natural landscapes, he said, calling for greater funding by Congress and state lawmakers to make sure federal, state and local public land managers can keep ecosystems healthy.

Much will depend on how fast humans address climate change. Another decade of burning fossil fuels, emitting more heat-trapping carbon dioxide and other gases into the atmosphere, “doesn’t bode well for humanity and for biodiversity,” Fielder said. “We can’t stop climate warming, but we can slow it. There’s a difference between a place that is 120 degrees versus a place that is 100 degrees. That increment could make all the difference….The sooner we get out of the oil and gas business, the sooner we are not part of the problem.”

Meanwhile, on his 20 acres of forest and wildflower meadows, Fielder has been basking in the beauty of a place he has protected, stars still visible in the darkness of night, away from traffic and industrial noise, wonders of evolution over 4 billion years on display.

He counted the elk that surrounded his house — more than 30. The mountain grouse at the door, the first of spring, sang as if wild birds no longer were imperiled.

“With this cancer now, I realize how fortunate I am to be in a place like this,” he said. “It makes all the difference in the world, being in the middle of nature.”

Get more Colorado news by signing up for our daily Your Morning Dozen email newsletter.

©2023 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at denverpost.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

[ad_2]

:focal(1405x1057:1406x1058)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/3d/583dcc03-3d6e-44e0-9ed5-c794761dbc5a/jun2023_b01_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/92/5f9255de-aff3-4305-9b02-8534d1aa92d8/jun2023_b23_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/f4/cff45bf3-6b79-4058-a60d-9c03a06ec60c/jun2023_b24_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/df/56dfa55f-ba66-476c-9c55-879d76980039/jun2023_b25_prologue.jpg)