[ad_1]

Researchers and scientists at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology may have found an alternative to problematic lithium-ion batteries that sometimes explode or catch fire, especially at the cheaper end of the e-bike and e-scooter range.

A research team working in collaboration with Italian-based automotive component supplier Eldor Corporation, hopes its work means it’s hopes it’s close to winning the global race to find cheap, rechargeable batteries.

“There are definitely a lot of companies and researchers looking for replacements,” lead researcher, Dr Shahin Heidari, told The Fifth Estate.

“I’ve seen sodium batteries, cobalt batteries and other solutions relying on sources of the elements, which can be either not environmentally friendly or become scarce – whereas the proton battery just needs hydrogen and carbon, a concept I have never seen anyone else do.”

Lithium-ion batteries are widely used for rechargeable batteries in everything from mobile phones, laptops, smart watches and power tools to e-bikes and e-scooters. But as The Fifth Estate heard at its Festival of Electric Ideas masterclass #2 Kit and Fit, around 450 of these e-mobility solutions have caught fire in Australia in just 18 months, causing fire experts serious concern.

Product Safety Australia has also flagged concerns of fire and even explosion if the lithium-ion batteries are poorly manufactured, handled, stored, or disposed of. Case-in-point the well-known phenomenon of a few years back: the exploding Samsung phones.

The proton battery, by contrast, offers a carbon neutral alternative.

Lead researcher Professor John Andrews said it splits water molecules to generate protons, which bond to a carbon electrode.

“When discharging, protons are released again from the carbon electrode and pass through a membrane to combine with oxygen from the air to form water – this is the reaction that generates power,” Andrews said.

“Our proton battery has much lower losses than conventional hydrogen systems, making it directly comparable to lithium-ion batteries in terms of energy efficiency.”

Dr Heidari, told The Fifth Estate that “in a lithium-ion battery, lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging.”

The proton battery is very safe by comparison – now for the development phase

“Compared to Lithium, proton is very safe, works under ambient pressure and environment and works better in higher temperatures because of the concept of charge and discharge,” he said.

The team has patented the latest development in this technology internationally.

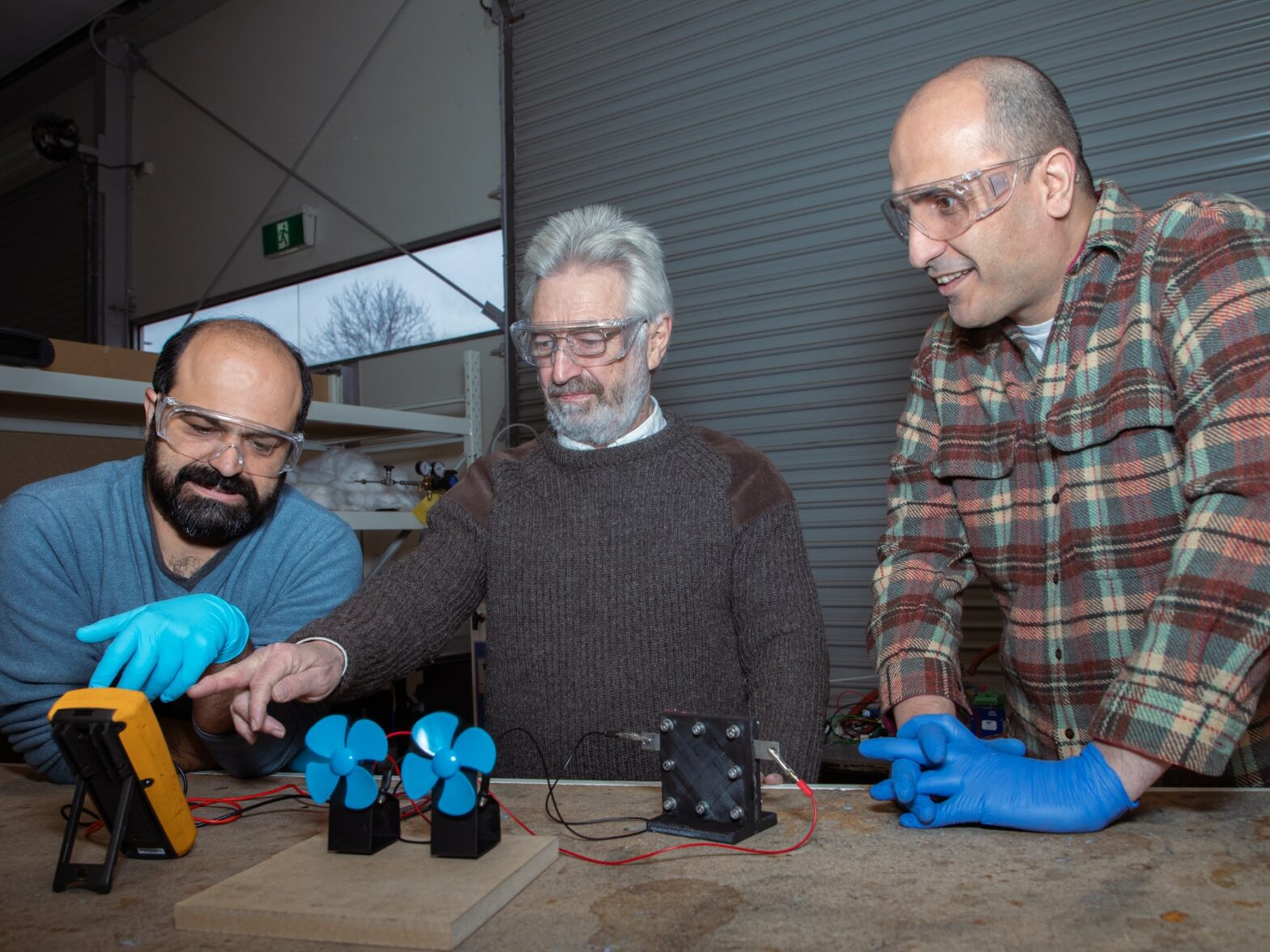

“While we are working on making the prototype, our industry partner, Eldor, will work on testing the proton battery on different products,” Dr Heidari said.

“At the moment, we’ve managed to connect the battery to smaller products like fans and led lights,” said. “Bigger products are still a work in progress as we haven’t tested the maximum output of the battery.”

The RMIT team hopes the battery will one-day power homes, vehicles, and devices without the end-of-life environmental challenges of lithium-ion batteries.

“Our dream is for these batteries to be on the biggest scale possible, for them to replace energy storage devices at houses and supply home appliances,” added Dr Heidari.

The environmental difference between proton battery, lithium-ion and every other rechargeable battery

Dr Heidari told The Fifth Estate that the main problems with lithium were:

- Mined from the Earth

- Extremely limited as a resource

- Recycling stumps even Dr Heidari – “it’s hard to know how much of the lithium is reusable after battery contamination”

Meanwhile, this is how the proton battery delivers where lithium-ion fails:

- Proton batteries are powered by renewable energy stored in carbon

- All you need to do is split atoms from water, carbon from wood and energy from the sun – resources that need to be used more often, according to Dr Heidari.

- Proton uses recycled parts, and materials can be rejuvenated, reused or recycled

While the structure and concept of charging and discharging differ, the proton battery competes with lithium-ion batteries with fast charging and discharging capabilities.

The Future is closer than you think

Professor J Andrews says that their latest battery’s storage capacity of 2.2 weight per cent hydrogen in its carbon electrode is more than double other reported electrochemical hydrogen storage systems.

“As the world shifts to intermittent renewable energy to achieve net-zero greenhouse emissions, additional storage options that are efficient, cheap, safe and have secure supply chains will be in high demand,” said Professor Andrews.

“That’s where this proton battery – which is a very equitable and safe technology – could have real value and why we are keen to continue developing it into a viable commercial alternative.

When asked when the RMIT proton battery will replace our iPhones, Dr Heidari and the research team said they are tentatively expecting the proton battery to enter the market in five to 10 years if everything goes according to plan.

“We all aim and hope for a world run on environmentally friendly energy,” added Dr Heidari. “Make the world a better place for us and our future generations.”

Related

[ad_2]