[ad_1]

Somewhere inside Oxford’s austere Weston Library, a vast, deep part of the city’s Bodleian Libraries that holds a fair chunk of its 13 million items, figures from the gloriously mahogany mid-1970s come to life. Angela Rippon, the newsreader, prances gaily in a chiffon dress; Margaret Thatcher smiles as only she can. David Hockney stands pensively beside a portrait of his own father, while Rudolf Nureyev sits in his chair, slightly tense. King Charles III, then Prince of Wales, grins in a carefree way not seen much in the five decades since.

“He is an unusually good-looking young man, better-looking than I thought from his pictures” read the notes on the royal sitting, which took place in March 1977. They are by Bern Schwartz, the businessman who made a surprising and successful late conversion to professional photography. He assures us that the future king has a “very, very warm manner”; Charles’s only request was that he not be called “Prince”. “In America, he’s called ‘Prince’ all the time,” records Schwartz. “Just as if someone was calling a dog.”

These are the brightest traces of the Bodleian Libraries’ latest big acquisition. They have been given Schwartz’s entire archives – a time capsule of 1970s portraits, negatives, faded typewritten notes, thank-you letters and Schwartz’s favoured camera (a Hasselblad medium-format) – alongside a gift of £2mn by The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation, now headed up by his three children and a family friend. If the Foundation has already given gifts and prints to various non-profit institutions, as part of its aim to preserve Bern’s legacy, this is its biggest cash donation ever. It has allowed the Bodleian to hire a curator of photography for the very first time, who will be able to marshal a huge and disparate holding that ranges from William Henry Fox Talbot’s personal archive to extensive photography of the anti-apartheid movement.

“It’s going to make us an institution that’s as well regarded as the V&A or the National Portrait Gallery for photography,” says Phillip Roberts, the man who has been hired as the Bern and Ronny Schwartz Curator of Photography. In the library’s hushed low-lit rooms, he unpacks the archive – much of which, such as the sitting notes and correspondence, has not been seen before. The gift will also lead to other archive acquisitions (he is in final-stage talks for four more) and several photography exhibitions; the archive itself will go on show in 2025.

The gift also preserves the legacy of Schwartz, who went from being a penniless youth in the Great Depression to a very rich man who got to photograph John Gielgud and Golda Meir, Margot Fonteyn and Edward Heath, “Kiwi [sic]Te Kanawa” and Cardinal Basil Hume. Not bad when you consider that he had his first proper lesson in photography in 1973, when he was nearing 60. The notes from his classes with the great Philippe Halsman are in the gift too, plus correspondence typed up by Schwartz’s ever-supportive wife Ronny. “To have the notes and the negatives from the working process… that’s what makes it really special,” says Roberts.

Bern Schwartz was born in New York City in 1914 and raised in Allentown, Pennsylvania. His father died when he was 18, forcing him to immediately get to work. It was hardly a propitious time – but it was also the end of Prohibition, and the young Schwartz got a job selling beer trays to a newly alcoholic nation. It led to many successful business ventures for a man who seems to have mixed suave, calm charm with a whirling restlessness. Eventually Schwartz would buy a textile manufacturing company in 1954, which led to him making a substantial fortune; he sold it to Standard Oil of Indiana in 1968. The Schwartzes began to split their time between La Jolla, California and London; it was also now that Bern could start photographing in earnest. He had always loved it: he bought his first Kodak aged 14. Soon, Schwartz used his contacts to get sittings in London, and the results would go so well (Thatcher used a portrait for an electoral campaign) that new sitters would appear by word-of-mouth.

“He wanted his pictures to be a ‘visual biography’ of the person,” says his son Michael. “He wanted the person to be engaged in expressing themselves, and to show their greatness.” To him and his siblings, it was obvious the archive should go to the Bodleian Libraries. “It has been around for a few hundred years,” he says. “Chances are the photography is in good hands.”

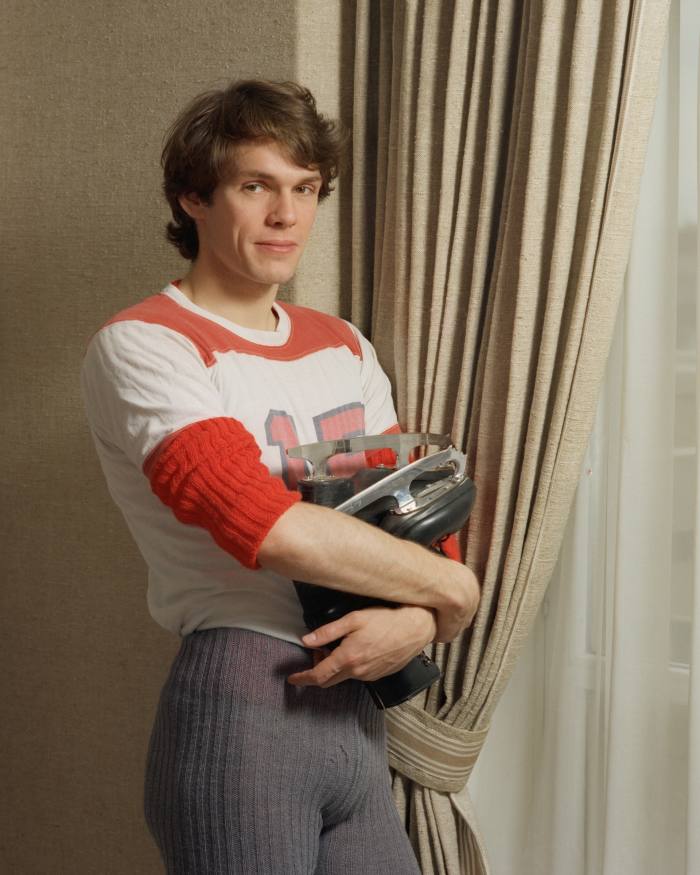

Both Michael and Roberts affectionately use the same term to describe Schwartz’s approach: tunnel vision. He seems to have needed it to court and cajole his famous faces. According to his notes, most meetings seem to start by someone saying how busy and tired they are: Henry Moore is “harassed”, Zandra Rhodes is “quite drowsy”, Rudolf Nureyev is “exhausted”. In fact, the ballet superstar looks “like a walking zombie” after a round of endless performances and partying. Hockney, meanwhile, forces Schwartz out of his comfort zone, as the photographer tries to incorporate the artist’s own painting of his parents into the shot; countless negatives show how the two work together. Yet somehow, the sitting always seems to end in effusive thanks and invitations to tea. Schwartz’s means of seduction vary, but it’s notable that the Prince of Wales, Nureyev and Lester Piggott are each asked if they like “body surfing”, a late passion of his discovered in California. Broadly, they do.

There is another touching comment in Schwartz’s notes on the Prince. “I also told him about my philosophy of life,” says the photographer. “That no matter what age I died, whether it was next year or when I was 100, I hoped that I would die young and that this meant just exercising and keeping very involved in activities.” The following year, in November 1978, Schwartz was due to be in Rome to photograph the new pope, John Paul II. However, the 64-year-old abruptly had to cancel in order to fly back to California to have treatment for pancreatic cancer. Six weeks later, on 31 December, he was dead. Michael, who was 30 at the time, eventually decided to interview many of his father’s business colleagues and family members to find out the source of his extraordinary drive. One told him that “working with Bern, you had a sense of satisfaction, because you felt like you were building something”. The large cache at the Bodleian Libraries suggests he’s set to keep doing the same.

[ad_2]