Of all the things America invented, the greatest might have been childhood.

The nation’s Child Labor Act of 1916 finally freed youngsters from toiling in factories or laboring in coal mines. The post-war prosperity of the ‘50s gave tweens and teens pocket money, social lives, and freedom. After years of being seen as simply smaller adults, by the mid-20th century children were finally fully themselves.

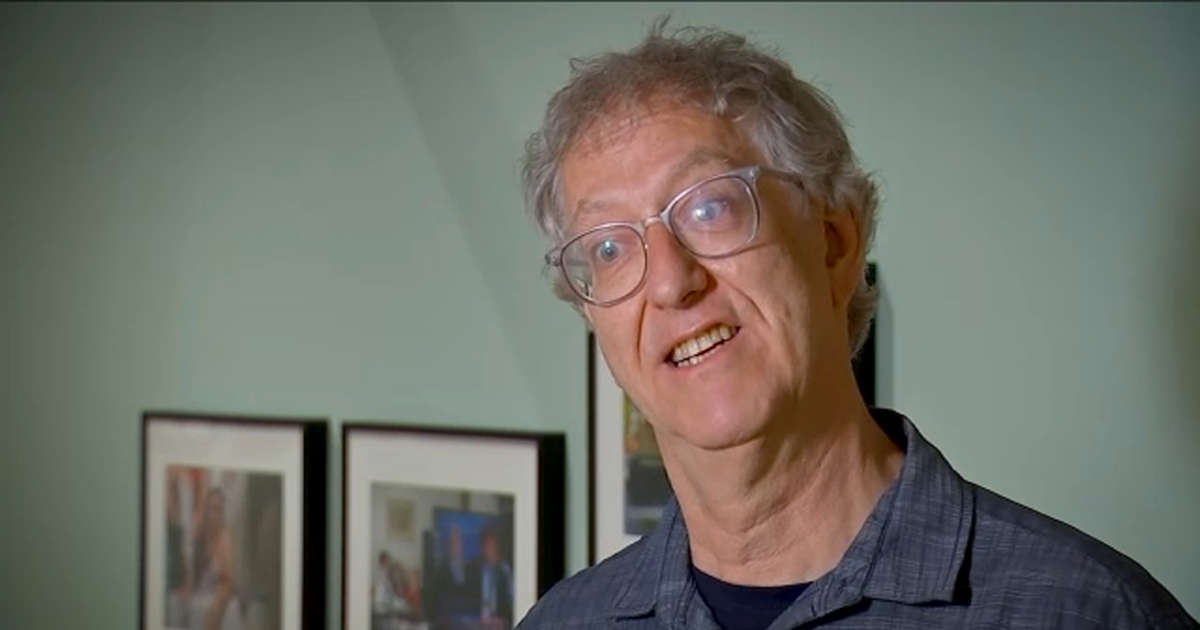

Those are among the insights in Todd Brewster’s “American Childhood: A Photographic History.”

It’s a sometimes lovely, often saddening saga of centuries of kids at play and work, skipping in the sunshine or struggling to survive. And it all began with Brewster’s massive treasure hunt.

“Over the past five years, I have been gathering up vintage images of children, some that stared out at me from piles in well-picked-over baskets at flea markets and thrift shops,” he writes. “I looked through the work of the world’s most distinguished photojournalism agency, Magnum … I skimmed community bulletin boards.”

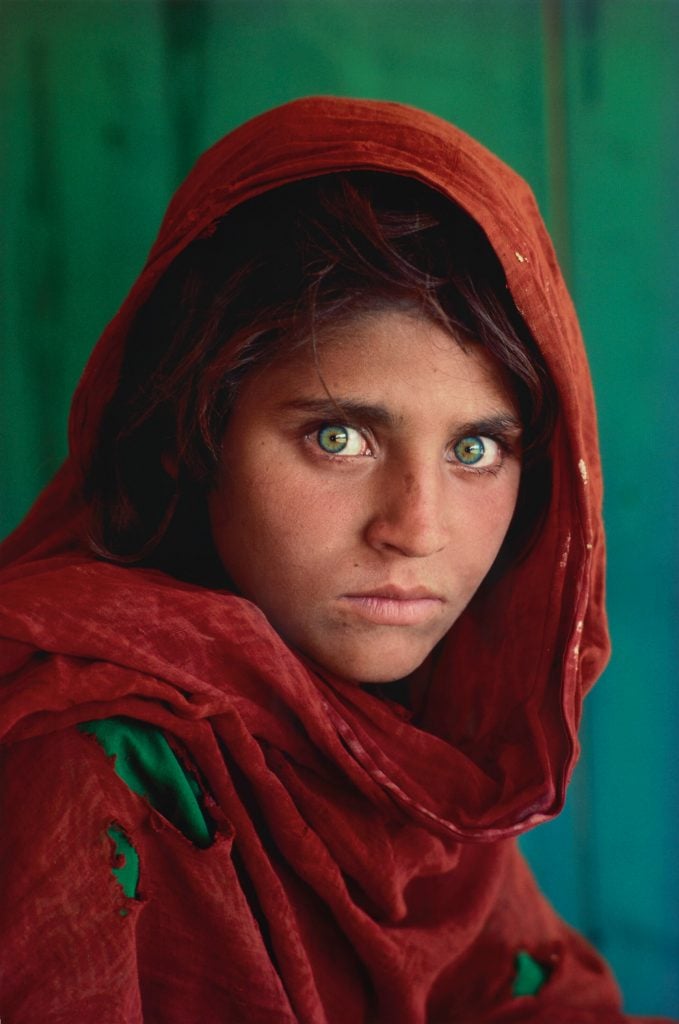

His goal, he writes, was to see childhood “through the eyes of children.”

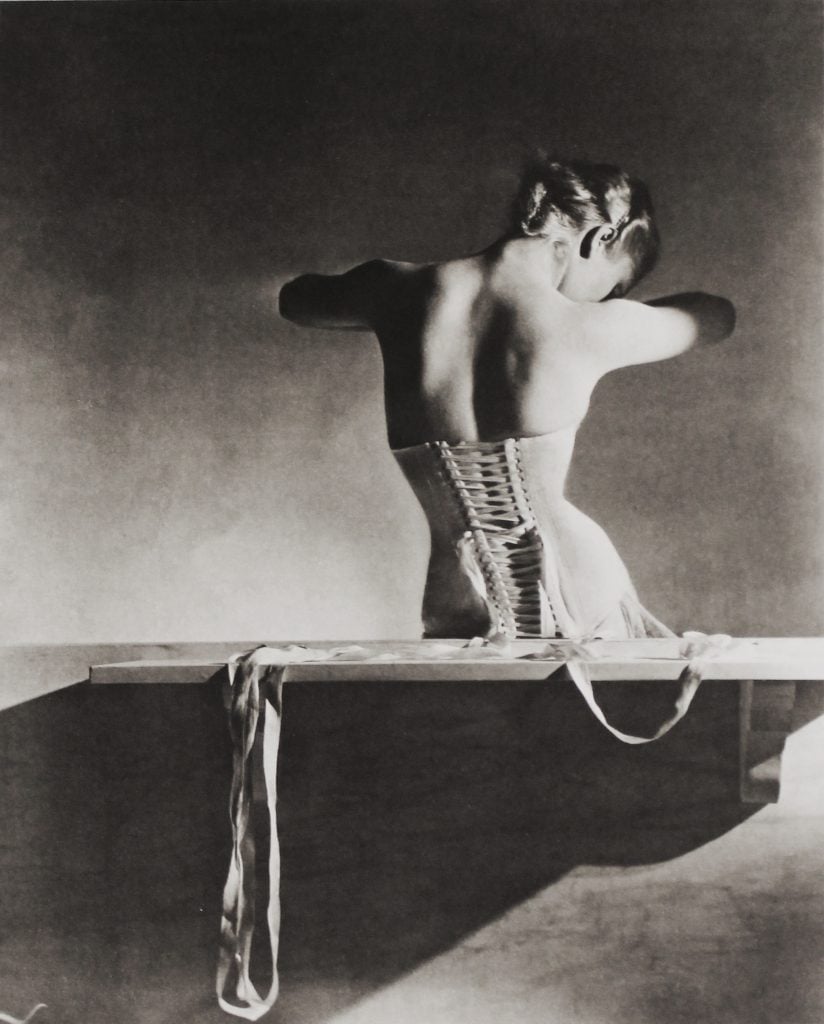

What they saw wasn’t always pretty, as some of the earliest photos show.

Johnny Clem was only 10 when he joined the Union Army as a “regimental mascot and emergency drummer boy.” The youngest soldier in the Civil War saw action at the Battle of Chickamauga, even wounding the Confederate officer who tried to take him prisoner. Luckily, Johnny survived the war and went on to a military career, rising to the rank of brigadier general.

Unluckier was Edwin Jemison of the 2nd Louisiana Infantry Regiment, who signed up at 16 and promptly perished at the 1862 Battle of Malvern Hill. “Nobly did he, although but a child in years, sustain himself in the front rank of the soldier and gentleman until the moment of his death,” according to his admiring obituary in the Southern Recorder. He was buried on the battlefield.

America grew quickly after the Civil War, and the labor of children helped that growth. They sewed clothes, picked cotton, and hunted whales. By the turn of the century, 2 million people — roughly a fifth of the workforce — were under 15.

In 1907, a private organization, the National Child Labor Committee, hired pioneering photojournalist Lewis Hine to document those lives. “Hine’s pictures showed weary children younger in years than their wounded faces would suggest, often with bodies badly disfigured and torn,” Brewster writes.

One nameless girl stands stoically between rows of machines in a South Carolina mill. One boy displays a roughly bandaged hand; he lost two fingers in an industrial accident. When factories barred Hine from entering, he would “follow them home, where he discovered working families living in squalor. The resulting photos served their purpose.”

Life may have been less physically dangerous for Richard Pierce, a messenger for Western Union, but he was already an old man at 14, scowling suspiciously at the camera. Pierce, Hine noted in 1910, works 11 hours a day, and during his time off, “smokes and visits houses of prostitution.”

Pictures like Hines’ helped show the actual cost of child labor, and eventually, legislators began putting new safeguards in place. Poverty remained in place, too — as photographs here of the Great Depression or the segregated South — prove. But the book’s photos of children at work begin to give way to pictures of them at play or school.

A photo from a 1948 story in Life magazine on the “kid geniuses” at the still-new Hunter College Elementary School depicts its gifted children. The day the photojournalist visited, the original caption explains, she found “a seven-year-old presenting a lecture to the school’s science club on the behavior of neutrons in uranium, a six-year-old summarizing her library research on the nature of time, two other seven-year-olds playing chess, and a ten-year-old girl learning how to conduct an orchestra.”

A picture from another school, the Intercommunal Youth Institute in Oakland, Calif., was founded to educate the children of Black Panther Party members — and to indoctrinate them in “the true nature of this decadent American society.” Taken in 1971, the photograph shows 12 young students standing at attention, wearing uniforms and signature Panther black berets. Party founder Huey P. Newton looks down on them from a poster on the wall.

There are also shots of children in less structured, more unguarded moments. A young girl cuddles her kitten, surrounded by the rubble of a house destroyed by a Missouri tornado in 1957. Deep in parallel play in 1987, several children supervise the toy trains at Manhattan’s F.A.O. Schwarz. In 1970s Little Italy, teenagers, alternately awkward and cocky, clown and court at a public pool. In 2014 Texas, adolescent cowpokes solemnly prepare for the Youth Bull Riders World Finals.

Some photos demonstrate stark contrasts. An image from 1957 shows a family in Reidsville, Ga., proudly decorating their car for a Knights of the Ku Klux Klan parade, their little girl eager to help. There, in 1961 Jackson, Miss., are the mugshots of two teenage freedom riders. The white teen, Margaret Leonard, was 19. The black child, Hezekiah Watkins, was 13. When arrested, he was locked up with adult criminals.

“The only thing I want to do is see my mother,” he told a reporter. “I recall crying every night and every day.”

These teenagers, fighting for voting rights, were heroes but never celebrities. Other children pictured here became famous later, sometimes through violence — there’s a photo of a youthful Unabomber — but more often through an enormous talent. Little Lady Gaga poses in front of the family fireplace. Young Janis Joplin shows off her Bluebird uniform and cracks an enormous grin.

There are pictures of a baby Lucille Ball and child stars Judy Garland and Shirley Temple. As she reached adulthood, Temple discovered that “her father had squandered the millions that she had made.” Another star who started very young was comic genius Buster Keaton. At age 3, he was hauled onstage to join his family’s vaudeville team; much of the act involved his father throwing the resilient toddler around the stage.

Child welfare agencies were concerned, but “we always managed to get around the law,” Keaton coolly explained years later. “The law read ‘no child under the age of sixteen shall do acrobatics, walk wire, play musical instruments, trapeze’ – and it named everything. But none of them said you couldn’t kick him in the face.”

Keaton spent his life in show business. He would go on to make and lose fortunes. But no matter how famous or how much he earned, was his childhood all that different from the little girl forced to toil in the cotton mills of South Carolina? Did he have a childhood at all?

“What have we learned from children?” Brewster asks. “The most obvious lesson is that we have not always appreciated children for their own sake; in fact, we have rarely done so. Instead, we have abused children we have profited from them. We have dismissed them as inconsequential … Most of all, we Americans, like centuries of other peoples who came before us, have asserted the primacy of those things that children need to learn from us — and only rarely reflected on what we might learn from them.”

©2023 New York Daily News. Visit nydailynews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.