When Henry Yee arrived as a young boy in early 1970s New York City, he did what so many kids in the Big Apple do: He became a Yankees fan.

But his interests extended beyond the Bronx Bombers. Yee became enamored with old photos of New York, images of skyscrapers rising into a skyline built over a century, and life in America’s largest city as it evolved across the decades. He also loved vintage photos of iconic Yankees ballplayers — particularly Babe Ruth. By the 1980s, he was taking photography courses and began buying old photos of New York and of its ballplayers.

“I merged the two interests together,” Yee said. “Back then, there weren’t too many collectors of this stuff.”

And because it was a niche hobby, outside the refined world of fine art photography collecting and the older pastime of trading cards, it was a chaotic wild west of random pricing and no universal system of authentication — was that Ruth photo taken and developed while he was still playing, or developed off a duplicate negative many years later? Or was it a total fake?

“There always was a problem in our hobby,” Yee said. “There was no system for how we sell photos.”

By the 1990s, original vintage sports photography began coming into its own as a serious hobby, and what brought it wider attention was the famed September 1996 auction by Christie’s in New York of hundreds of images from “Baseball” magazine’s photographic archive that spanned 1908 through World War II and featured images of baseball’s greatest players of the era shot by the most famous baseball photographers, such as Charles M. Conlon.

“That’s when a lot of material was put on the market for the first time,” Yee said.

What took the hobby much closer to the far more structured universe of graded trading cards was Yee and a couple of collector friends, Marshall Fogel and Khyber Oser, assembling the 2005 book “A Portrait of Baseball Photography.”

But it wasn’t a coffee table book of vintage images. It systemized how to grade original sports photography.

And thanks to that system, which allows images to be “slabbed” in a plastic holder with condition and grading data like a trading card, the vintage photography hobby has become a genre of sports collectibles that produces eye-popping sales prices that can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In the book, Yee and the others created what’s known as “The Photo Type Classification System” and in 2007, PSA (one of the major card-grading companies) licensed the system to create an authentication and grading service for old photos. Yee was hired to run PSA’s photo grading and authentication service.

“To get to the next level, someone had to create a system to give it structure. With cards, you had that organization,” Yee said. “There was no third party, which gives it a boost and gave confidence to those not collecting those items to come in. Once it’s graded, it becomes a commodity that can be traded sight unseen.”

The system they developed grades photos as Type I through IV based on the negative and when it was developed from that negative. The best is a Type I photo, which means the image was developed from the original negative within two years of that image being shot, while a Type II photo is made from the original negative after two years from the negative’s creation.

Type III and Type IV photos are made from duplicate negatives, not the original, and are graded as either within two years of the duplicate negative’s creation or after two years. Those have much less value than Type I and II.

The system is now the foundation of original sports photography buying and selling.

“Took a few years to get momentum, and by 2012-13 it started picking up,” Yee said. “It was shocking to us that it was so widely accepted. You had a framework that allowed the hobby to grow.”

Unlike trading card collectors, original photography buyers expect some wear and tear or editorial marks — grease pencil lines for cropping, agency and filing stamps, notations, paper captions, etc. — on the physical images because the photos were used in practical ways and were not intended as collectibles. And if the marks came from a noted photographer, that could add further provenance and value to the image.

“People appreciate photos that were practically used and have the evidence of behind-the-scenes editorial work,” said Oser, Yee’s co-author and now the director of vintage memorabilia and photography at Goldin Auctions. “That’s not a liability, that’s not a detriment. … For now, at least, condition is secondary.”

Original sports photography has been growing in popularity on the shoulders of the wider collectibles surge that’s been underway for several years, particularly among trading cards that have seen some sell for as much as $12 million.

“Original photography has benefitted from the card boom,” said Robert Edward Auctions president Brian Dwyer.

Earlier this month, Robert Edward Auctions sold a Type 1 Josh Gibson photo from the 1940s when he was with the Homestead Grays, an image used for his 1950-51 Toleteros rookie card, for $150,000. In the same auction, a circa 1913 original photo of “Shoeless” Joe Jackson of the Cleveland Naps, graded Type 1 and shot by Conlon, sold for $132,000 while a Type 1 1947 Jackie Robinson rookie photo — taken the day after he broke baseball’s racial color barrier as a Brooklyn Dodger — sold for $32,400, the auction house said.

This Type I photo of Jackie Robinson, taken one day after he broke MLB’s color barrier, sold for $32,400, Robert Edward Auctions said. (Courtesy of Robert Edward Auctions)

“We’re seeing the number of photographs come to market increase, but also the number of people bidding increase,” Dwyer said.

Like with cards, rarity drives interest and price, and photos have a more defined era of physical availability than cards. Photographers were limited by their film stock — a camera held only so much film — until digital photography started to become widespread in the 1990s and shooters could take literally endless numbers of photos.

“The rarity factor is gone,” said Rob Rosen, the vice president of sales and consignments at Heritage Auctions.

Hence, original sports images starting with the rise of baseball (and photography itself) around the time of the American Civil War through the end of the 1980s is the general collecting period.

What most often drives price are the celebrity of the player, the age and rarity of the photo under the classification system, and if the image has historical significance linked to a milestone event.

“The first million-dollar photo … turned out to be a 1951 Bowman card-used photo (of Mickey Mantle), I think in a private sale,” Oser said. “Six-figure photos are more and more common, and we will certainly be seeing more million-dollar photos.”

Who took the photo also can significantly goose value.

One such shooter was Conlon, who took an estimated 30,000 baseball photos until his retirement in 1942. His archive of more than 7,400 fragile glass plate and other negatives sold through Heritage Auctions in 2016 for $1.79 million.

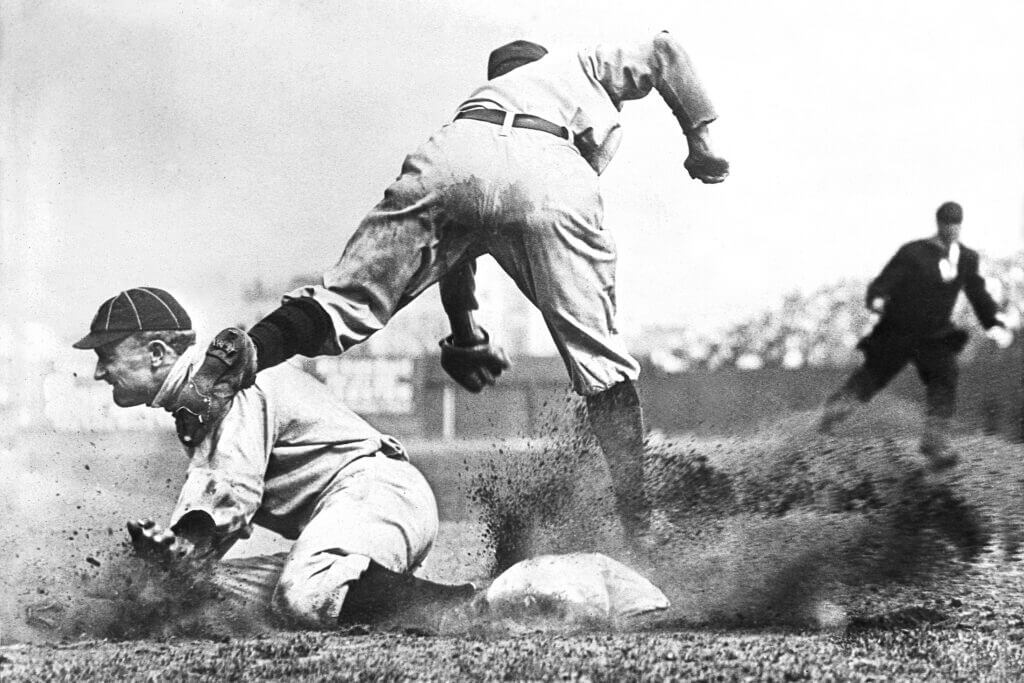

Conlon, who mostly took portrait shots of players, is perhaps best known for an action photo of Detroit’s grim-faced Ty Cobb sliding into third base on July 23, 1910, at New York’s Hilltop Park — the Highlanders’ home stadium until 1912, a year before they became the Yankees — with infielder Jimmy Austin failing to tag him amid a small explosion of dirt around the bag.

An original image developed by Conlon off the negative he shot that day for the New York Evening Telegram sold for $390,000 via Robert Edward Auctions in December 2020.

Even outside the major auction houses, vintage original sports photos are priced at big numbers.

On eBay as of this writing, there’s a PSA-graded Type I 1923 photo of Lou Gehrig that’s possibly the earliest photo of him in a Yankees uniform, and it’s listed at $500,000 with 49 people labeled as watching the listing. Next after that is a listing for a 1919 Babe Ruth photo for $125,000.

Auctioneers said modern sports images taken from negatives sell for much less than the vintage stuff, but value can still be found from early images of top-tier athletes such as Michael Jordan, particularly of the photo used for his much-sought 1986 Fleer rookie card.

While loose, framed, or mounted vintage photos used to be the only way they were sold for years, the ability to get images authenticated and graded in plastic holders (known as slabs) streamlined the hobby, with PSA as the only major firm doing such work.

“Slabbing always helps everything,” Rosen said. “We’ve sold some (original photos) for half a million dollars.”

The hobby isn’t limited to enormously expensive cards. Collectors can buy lower-graded photos for much cheaper prices, even under $100, but famous players may still be pricey even at the lesser type levels.

“Collectors underappreciated Type II and III photos for many years, and now you see Type II and IIIs being affordable alternatives to important historical images,” Oser said. “The value is there now. We are selling Ruth and Gehrig Type IIIs in the thousands of dollars.”

And much like the trading card world’s scandals, original sports photography has experienced its share of fraud and swindlers.

For example, the baseball photo archive of Chicago’s George Brace, who died in 2002, was sold for $1.35 million in 2012 but the deal ended up in lawsuits over non-payment, and the buyer, vintage news and sports photos and memorabilia collector John Rogers, in 2017 pleaded guilty to running a fraudulent operation and was sentenced to 12 years in federal prison and ordered to pay $23 million in restitution.

“There’s a seedy underbelly to baseball photography,” Oser said. “All these industries had their wild west period before professional authentication became the sheriff in town.”

Authentication is intended to help offset deception as the hobby matures. PSA has invested in resources and staffing as sports photography collecting has continued to grow, Yee said, with more space devoted to his department and a dozen staffers working under him.

“We have grown double every year for the past five years, in submissions and revenue,” Yee said. He didn’t disclose financial specifics.

Babe Ruth photos, like this Type I from the 1910’s, are the star attraction. “He is the guy in our hobby, the king,” Henry Yee says. (Courtesy of Robert Edward Auctions)

PSA is owned by Collectors Universe, which since its 1986 founding has created a number of sports and non-sports collectibles third-party authentication and grading services. Billionaire New York Mets owner Steve Cohen led an investment group’s purchase of Collectors Universe for $850 million in early 2021 and then bought Goldin Auctions as a standalone business several months later for an undisclosed sum.

That means PSA and one of the major auction houses are linked, which can raise eyebrows, but the photo grading system has been widely accepted across the industry. Trust is critical.

The authentication process is rooted in experience, Yee said, and practical research and technical investigation with powerful microscopes and other technology. In addition to basic eye tests, PSA has a library of thousands of photo paper samples and hundreds of photo agency stamps against which researchers can index an image. Yee calls it a fossil record and noted, “the paper doesn’t lie.”

“You see enough of something, you know right away. There are signs to look for. It comes from experience,” Yee said. “We can identify a photo right away. Some of it, we can’t. We’re still learning.”

Baseball remains the most popular sport among submissions and collectors, Yee said, but there’s been an uptick in other sports, including football, basketball, hockey and soccer, in recent years.

“The most expensive photographs are going to be baseball,” Yee said. “It’s always been that way. It’s always vintage baseball.”

The most money for single vintage images mirrors what’s the big driver in baseball cards: rookies.

“(That) is where the market has matured,” Yee said. “That gap has widened so much, with the rookie images selling for 10, 20 times as much (as later photos of players). People have started to realize that the early images are the hardest to find.”

What’s the so-called white whale of old baseball photos?

“The holy grail image is probably the Honus Wagner image,” Yee said. “It probably would blow past $5 million.” The auctioneers and others agreed.

Boston photographer Carl Horner shot Wagner in a studio around 1902 and the portrait was later used for the famed T206 Wagner “tobacco” card from 1909 that has been one of the most famous and expensive rare cards of all time. A few prints of the Wagner photo have sold for thousands of dollars in varying conditions, and the original image is said to be rarer than the trading card (a Wagner T206 sold in 2021 for $6.6 million).

Babe Ruth remains the most popular player among vintage photo collectors, Yee said, and in February a 1915 image of The Babe sold for $468,000 via Robert Edward Auctions.

“He is the guy in our hobby, the king,” Yee said.

What vintage sports photography is missing that the trading card industry relies upon, particularly for the most rare and expensive items, is population reports. Those are lists of graded things and their sales prices — easy to do with cards because of known print runs and other data from manufacturers and collectors. But with photos, it’s usually impossible to know how many prints may have been made off a glass plate negative.

While PSA is working on some yet-to-be-disclosed efforts in that vein, true pop reports may be impossible, Yee said.

“The big challenge is cataloging it,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s logically possible and economically feasible.”

And the future of vintage sports photography collecting?

It’s obviously in the best interest of PSA and auction houses to be publicly optimistic, but it’s true that the overall collectibles boom — estimated to hit $35 billion this year — has continued and is expected to for some time. While any collectibles genre is subject to market forces and the whims of the public (hello and goodbye, sports NFTs) high-end commodities such as fine art, wine, cars, stamps, etc., have traditionally retained their value in the face of inflation and recessions. There are only so many Conlon and Brace Type I images left.

“The best of the best stuff will always continue to go up. It’s a finite amount of stuff,” Yee said.

GO DEEPER

State of the sports card boom: After sky-high surge, is market still healthy?

(Top photo: Charles M. Conlon / Sporting News via Getty Images Archive via Getty Images)