[ad_1]

On her first trek through the rain forest, in 2000, the artist Catherine Chalmers noticed movement on the ground near her feet. It was a parade of thousands of leaf-cutter ants. “There’s these perfectly cleaned pathways that the ants make and maintain, and they carry bright-green leaves,” Chalmers told me recently. “And so you saw this ribbon, almost like a drawing. Green, flickering, because light shimmers on them. I didn’t know they existed. And it was really, really beautiful.”

Chalmers wanted to work with the ants, but didn’t know how. “I’m interested in that place where nature meets culture,” she said. The more complicated the interface, the better: around this time, she was exploring humans’ relationship with cockroaches. But, by comparison, the ants seemed almost too natural to work with artistically. “They’re of the forest,” she said. “We think of them as the other.” What would it mean to make art about our relationship with such creatures?

Chalmers mulled over the idea for years, steeping herself in the science of leaf-cutters. The more she learned, the more connections she saw between them and us. While the ants may be of the forest, they’re also intensely social—urban, even, in their extensive underground lairs. In a 2011 book, “The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct,” the biologists Bert Hölldobler and Edward O. Wilson suggest that “if visitors from another star system had visited Earth a million years ago, before the rise of humanity, they might have concluded that leafcutter colonies were the most advanced societies this planet would ever be able to produce.” For two decades, Chalmers followed this trail of thought. Last month, we stood inside a culmination of that work—a solo exhibit at the Drawing Center, in SoHo, titled “Catherine Chalmers: We Rule,” which comprised twenty-four drawings, a twenty-foot photo print, four videos, and an installation, which together evoked how much both humans and ants have busied themselves dominating and altering their environments. (It ran through January 15th.)

Chalmers, who is sixty-five and has an athlete’s poise—in addition to being an artist, she’s an accomplished figure skater—led me through the gallery. On one wall, sixteen drawings depicted ants in chambers and tunnels that formed a larger colony. There are around fifty species of leaf-cutter ant, and nests differ among them, but a nest can span five hundred square feet—“As big as this gallery here,” Chalmers noted—sometimes reaching twenty feet below the ground and containing thousands of chambers the size of a cabbage. Inside, there can be millions of ants supporting a queen who survives for more than a decade.

Human agriculture has shaped the planet for millennia, but leaf-cutters began cultivating food at scale millions of years earlier. The ants are responsible for a quarter of all plant consumption in their ecosystems; worker ants might travel two hundred yards to collect leaf clippings, cutting tons of plant material a year. Back home, adults drink the leaf sap while feeding the clippings to a fungus that they grow in their nests. They then harvest the fungus, feeding it to their larvae. To prevent a different fungus from taking over their “fields,” some leaf-cutters cultivate bacteria that produces antibiotics which the ants spread around their garden—a form of pest control.

The ants demonstrate a “chemical mastery” over their environment, Chalmers said. But, at the same time, they are enmeshed in a symbiotic system. “We think the ants are calling the shots, just as we think that we are deciding, when we go to a restaurant, what we want to eat,” she told me. “But the more that I’ve read about the microbiome”—the bacteria and viruses inside us that keep us alive and sometimes make us sick—“the more it seems that microorganisms are greatly influencing the choices that we make.” There’s a sense in which the bacteria in our guts “want” sugar, and so we order ice cream. It’s possible that the ants’ fungal gardens act like their microbiomes, influencing which plants a colony forages. Perhaps it’s not the ants that “rule” the rain forest but the fungus. “I’m not a scientist,” Chalmers said. “So I can speculate on these things and just observe and wonder.”

At the heart of “We Rule” is a set of four videos about ants that evoke core aspects of human culture: language, ritual, war, and art. The filmmaking began in 2007, when an art collector who had seen Chalmers’s earlier work invited her to his private island off the coast of Panama, where he also hosts scientists. Chalmers accepted the offer once she learned that the island had leaf-cutters. Working outside the studio was daunting: to set up a shoot, she’d clear brush to avoid bites from snakes and scorpions, then dig a hole to view the ants at their level.

The language-themed film that emerged from the trip is a four-minute piece called “We Rule.” Up close, amid a cacophony of bird and insect sounds, we see ants munching through green leaves and pink petals. Then, somehow, they’re munching the leaves into perfectly trimmed capital letters; by the film’s end, the ants march along, conveying the titular message, while a chorus of howler monkeys cheers them on. (The film is not computer-animated; the ants really did carry tiny letters made by Chalmers.) Ants are always “sharing data,” Chalmers said—sending signals about threats, food location, and leaf quality through pheromones and vibrations called stridulations, which they create by rubbing parts of their bodies together. “Somehow, in this exchange, they go to war, they decide what they’re going to harvest, how many tunnels, how many chambers. And without central command.” The film gives the ants a chance to boast about their inhuman coördination.

The roots of “We Rule” go back to the nineteen-eighties. Chalmers was earning an M.F.A. at the Royal College of Art, in London; she’d come to admire cuneiform-inscribed neo-Assyrian tablets at the British Museum and elsewhere. She tracked down a translation of the cuneiform text. Essentially, it says, “with little variation, ‘We rule, we conquer, you suck,’ ” she told me. Working with the leaf-cutters, she thought back to the tablets’ imperialistic message. “They’re a little bit a stand-in for us,” she said, of the ants. Making the film, she’d hoped to induce them to carry ten passages from the tablets, but it took her two days just to get six letters in the right order.

Chalmers grew up in San Mateo, California, the daughter of an electrical engineer and a landscape painter. She wasn’t into bugs as a kid, but the family liked animals; she had a bird, and brought it to breakfast and sleepovers. At Stanford, she declared her major, engineering, before classes even started, so that she could secure a spot in a popular course on visual thinking. She took almost enough studio courses to qualify as an art major and, after college, got a job at Mattel, designing toys. Her engineering background has helped her solve the puzzles of art production. How do you build a set that induces insects to behave a certain way? How do you film and light it?

Her work with insects began when she moved to New York, after her M.F.A. As an experiment, she started putting dead leaves and flies on her canvases; when she ran out of flies, she started raising them. The flies swarming in her terrarium entranced her, so she asked her neighbor to teach her photography. He lent her equipment, which she used to make her first book, “Food Chain.” At first, she was a little sickened by the idea behind the project: “I was going to raise animals to feed to another animal,” she said. “But, the more I thought about it, and the more horrified I was, the more it made sense, because one of the drivers of civilization is to remove ourselves or to have control over the food chain.”

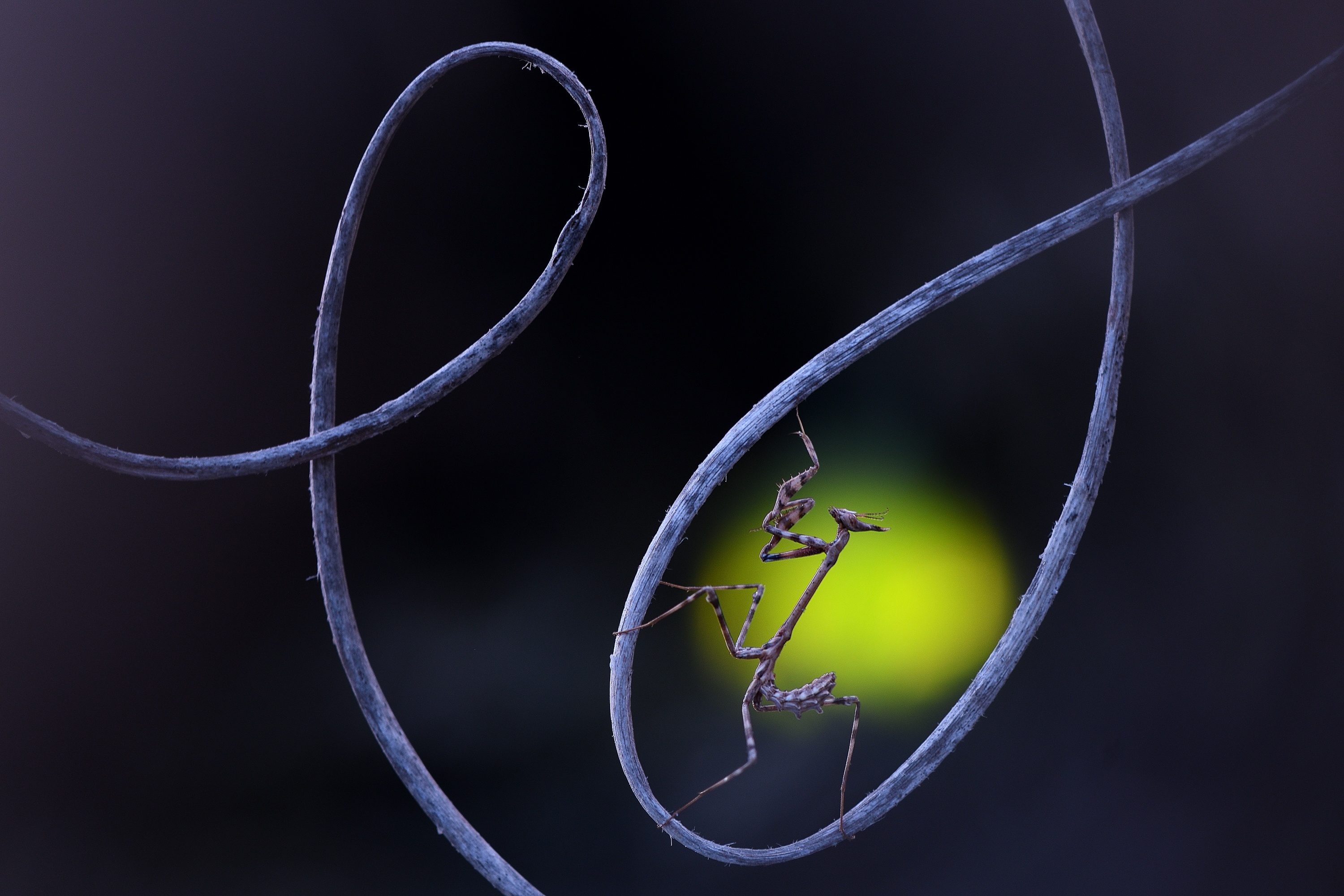

Chalmers started with a red tomato. She applied turquoise tobacco hornworms, which burrowed their way through the fruit’s juicy flesh; she then fed the hornworms to a praying mantis, which she fed to a frog. She also raised mice, feeding pink babies to a snake and a second frog. “Baby mice are like nature’s Cheerios,” she said. “I mean, everything eats them.” Starting in the early nineties, the photos were presented at shows around the country. “Boy, did I get hate mail,” Chalmers recalled. Viewers who could tolerate a photograph of a praying mantis shredding a larva drew the line at seeing a snake swallow a mouse whole. “Predation is essentially what keeps the ecosystem going,” Chalmers said. “There’s no way around it.”

She leaned into her own queasiness. “I would see a cockroach and I would lose it,” she said, so, interested in “our adversarial relationship with nature,” she began making films and photographs in which cockroaches are disguised as more palatable creatures, or living in tiny houses, or being executed in a gas chamber or electric chair. One film, “Safari,” depicting the domestic bugs exploring a jungle, was called “perversely entertaining” and “deeply Darwinian” by Time Out and the Times, respectively, and won the 2008 Jury Award for Best Experimental Short at the South by Southwest Film Festival. The work encourages us to empathize with bugs. One reason they disgust us, Chalmers believes, is that they seem immoral, or at least differently moral. “We see ourselves as individuals,” she said. “And we see insects as being this uniform, formless mass that will sacrifice themselves and do all these sorts of things.” Some of her photos capture a praying mantis eating the head of her mate. “Civilization is a march for greater and greater and greater control over the world,” she said. But nature doesn’t play by our rules.

Another of Chalmers’s admirers owned many acres on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica, which contained multiple leaf-cutter colonies. The other three ant films were made there. “The dynamics between the colonies—it was a little bit like ‘Game of Thrones,’ where the same species in the same habitat had markedly different personalities,” Chalmers said. To make “The Chosen,” a film about ritual, in which ants carry flowers to a large golden idol of an ant, she collected flowers and presented them to all the large colonies within range of her lights. She coaxed certain ants into climbing over the idol, which scented it with their pheromones and would entice other ants to traverse it, before she placed it in a set depicting an underground chamber. The ants sometimes drop their flowers when they hit impediments. “And so they started burying the idol,” Chalmers said. “I thought it was perfect, because in a way it’s something that we wouldn’t do. It’s as if they’re burying their idol with nature, as if somehow nature trumps religion.” As the ritual proceeds, we hear the sounds of a Himalayan bell.

For her third film, “War,” Chalmers found a large colony that sent ants out each night. A smaller, neighboring colony had arrived at the opposite strategy, sending its ants out during the day and getting them home before nightfall. At night, some ants from the two colonies crossed paths; at the spot where they’d meet, she set out a white sheet and lights, then recorded the ants as they fought. As moody music plays, the film shows hordes of small ants ganging up on lumbering soldiers many times their size. The ants mince each other until only scattered piles of bodies and limbs remain. “You had this David-and-Goliath situation,” Chalmers said. The film is less than four minutes long, but the battles she watched would last for hours.

Chalmers sees the ants as her collaborators. In “Antworks”—the fourth film, which focusses on art—“their idea was much better than mine,” she said. Originally, in “War,” she’d planned to use time-lapse footage of ants stripping a branch, because “oftentimes the degradation of nature or the environment in a place leads to civil conflict,” but couldn’t get the ants to do it. Eventually, though, she noticed a colony near the beach stripping a colorful plant she’d thought was toxic to them. She used a machete to hack a branch off the plant and brought it back to her filming area. In “Antworks,” the ants lift the pieces, which are abstract and colorful in appearance, and then affix them to a flat rock wall. By the end, they’ve put nine striped and spotted leaf cuttings on the wall in a row, as if in an art gallery.

[ad_2]