[ad_1]

The old adage “the gift that keeps on giving” certainly applies to the Capital Group Foundation’s donation of 1,000 photographs to the Cantor Arts Center. Since 2019, the museum’s curators have organized several exhibitions from the gift on various topics, the latest iteration of which is “Reality Makes Them Dream.” Consisting of over 100 prints, periodicals and photo books from the 1930s, the exhibition is on view through July 30.

The majority of the photographs are, as one might expect, in black and white. They reflect the work of the five major artists in the collection: Ansel Adams, John Gutmann, Helen Levitt, Wright Morris and Edward Weston, as well as a number of lesser-known artists. The exhibition curator, Josie R. Johnson, explained the special strengths of the Capital Group gift as “the opportunity to study and present the work of artists in much greater depth. … The majority of the photographs in the collection were selected and printed by the artists themselves (or under their supervision) at later stages in their lives when they could look back at the full sweep of their careers.”

Johnson, who is the Capital Group Curatorial Fellow for Photography, reviewed the entirety of the collection before narrowing her sights on the 1930s. She said that this decade offered “a rich cross-section of the collection” but she also noted that there was a need to rethink the tendency to see this time period as rife with documentary-type images. “I developed the exhibition thesis that many American photographers created realistic images of the world around them to spur their viewer’s imaginations.”

In order to fully appreciate this thesis, it is necessary for the viewer to slow down and consider each print carefully and in detail. One might say that the placement of Dorothea Lange’s iconic portrait, “Migrant Mother,” is classic Depression-era documentary photography that we know well. But taking time to stand before the real print, instead of seeing a reproduction online or in a magazine, there are many details to consider. The mother’s worried expression as she looks vacantly to the left, the threadbare clothing on the children and the smudges of dirt on the baby’s face – he or she is barely visible in the folds of cloth. This is still an incredibly powerful image that sums up every bit of despair, sadness and futility of the environmental and economic disaster that was the Dust Bowl.

Johnson sees similarities from this decade to our own. “I hope people find inspiration in the way the artists saw the world at a time with parallel economic challenges, environmental catastrophes, and international conflicts.” And while pictures like Migrant Mother have come to symbolize an entire era then, as now, life did go on and there were beautiful, even wondrous things to behold.

Ansel Adams is usually thought of as the chronicler of the West and its open spaces. In this show, there are examples of his smaller, more intimate work. “Dogwood in Yosemite” is a spectacular print thanks to the high contrast between the lush white flowers and a black background. His well-known portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe and Orville Cox is always delightful to see, thanks to that mischievous grin on the painter’s face. And he even did still life, as can be seen in “Sculptor’s Tools,” a riveting study of line, texture and contrast.

Moving from print to print, there is a sense that what has been captured in black and white is a slice of Americana from a much slower and, perhaps, more innocent time. Berenice Abbott’s “Warehouse, Water and Dock Streets,” is a Hopper-esque study of stillness. We can imagine it might have been taken on a Sunday morning, given the lack of people and activity, but look closely in the center of the print at the seated man, casually reading his newspaper.

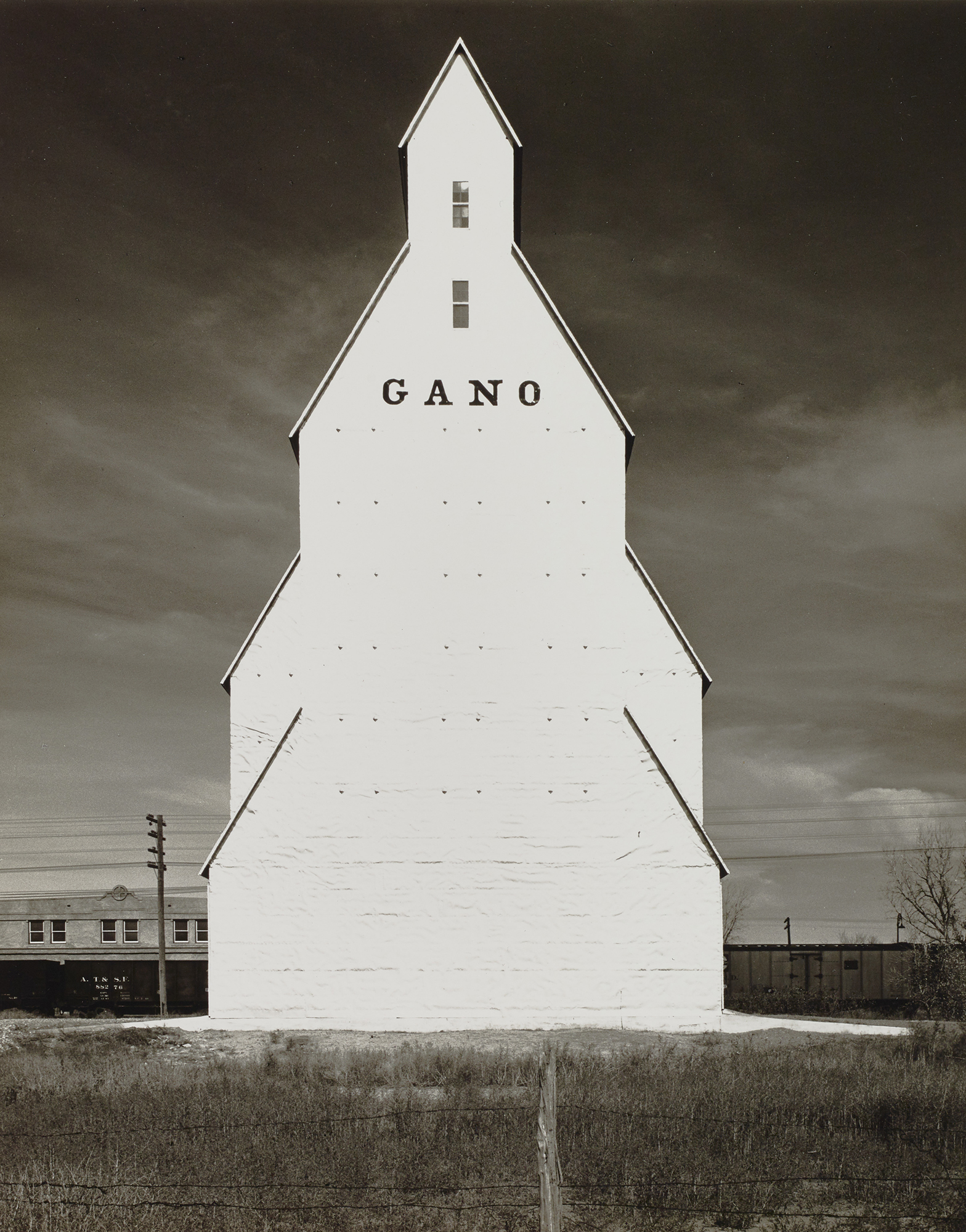

Wright Morris captures buildings and objects that were central to life at the time: the church, the meeting house and the barber shop. In the “Grano Grain Elevator, Western Kansas,” he elevates a humble farm building to the status of a rural cathedral, its symmetrical form reaching up to the heavens.

No exhibition from this time period would be complete without Edward Weston and he is represented here in all the ways we know him: portraits, still-lifes and landscapes. Whether it was an extreme close-up of a green pepper or the enigmatic shadows created by an egg slicer, Weston was a master of light and dark. Johnson shared that his “Nude (Charis) Floating” is her favorite image of the show. “This scene is nothing out of the ordinary, but the way Weston frames the pool and catches the light makes it seem otherworldly.”

In addition to Berenice Abbott and Dorothea Lange, several other women artists are represented. Ruth Bernhard’s take on the egg slicer is humorously titled “Kitchen Music.”

Margaret Bourke-White’s “Drilling Rig” demonstrates how imaginative framing and timing can turn an industrial site into a study in abstraction. Anne Brigman’s dark and moody “Nocturne” takes us to the beach at twilight. Marie Post Wolcott’s “Center of Town, Woodstock, Vermont” captures a snowy main street in small-town America. Noted Johnson, “This image is full of enchantment; the glowing orbs of light from the street lamps and the snow-dusted sidewalks make this photograph appear as though it was plucked from a snow globe or some other winter wonderland.”

It was not just the bucolic rural scene that these artists were drawn to; the city was also captured in all its glory and idiosyncrasies. John Gutmann was attracted by the signs and symbols of city life, while Helen Levitt’s street urchins display the need for fun and socialization, no matter what side of town you hail from.

We are now used to being bombarded with images that have been edited and revised in myriad ways. As this exhibition demonstrates, this was a simpler age. “These photographs offer useful representations of how these subjects appeared at the time, since all of these artists participated in the interwar-era shift from favoring staged, heavily retouched, and softly-focused photographs to natural, minimally edited and sharply-focused images,” Johnson said. “For many of them, it was the straightforward view of the scene before their lens, with just the right light or framing or composition of elements, that constitute a work of art.”

The exhibition ends with a well-known and much beloved image by Ansel Adams, “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.” It was taken in 1941 and America was about to enter into a global conflict that would have enormous impact on the social fabric of the country. But it is an optimistic picture, full of the wonder of the natural world that would, hopefully, survive for generations to come. Noted Johnson, “For those who think of the 1930s as wholly defined by the doom and gloom of the Great Depression, perhaps they will see how some people found joy and beauty in the world around them, difficult as it was.”

“Reality Makes Them Dream” is on view through July 30 at the Cantor Arts Center, 328 Lomita Drive, Stanford. Admission is free; reservations are required. For more information, visit museum.stanford.edu.

[ad_2]