[ad_1]

Savannah Dodd (32), who is originally from St Louis, Missouri, relocated to Northern Ireland in 2016 to be with her partner, who is from Belfast.

Savannah is the founder and director of social enterprise the Photography Ethics Centre and has recently completed a PhD in anthropology at Queen’s University.

Savannah Dodd at work

Her new photography exhibition, titled Slow Still Life, at Ards Arts Centre, embraces reconnecting with nature and slowing down to pay closer attention to the ordinary. It is also about unlearning perfectionism and the urge to be productive.

“I think a lot of this exhibition really stemmed from this move from the city to the countryside,” Savannah says.

“I was really interested in how do we manage this land? How do we steward this land in a responsible way? We’re really interested in permaculture and rewilding. So when we first got out here, we really wanted to learn about all these things and to connect with the land and with nature in a way that we hadn’t really had an opportunity to before, especially because we were travelling so much. We had a really international career pre-pandemic.

“The move really created a change in me as a need to slow down, but I also found a new appreciation for things I think I used to overlook, like slugs — there’s a photograph of a slug in clover in the exhibition. It’s the little things that we have a tendency to sort of forget about.”

During the pandemic, Savannah learned how to process film in her kitchen. As she began connecting with the natural environment around her, she went on to set up her own darkroom and learned the skills involved.

With a desire to document her experience, Savannah felt analogue photography was the best fit.

“Analogue photography is a skill that I gained during the pandemic through a grant from the Arts Council,” she says.

“That was sort of a new thing that I was practising and enjoying working with, but I felt like the slowness of it also made a lot of sense, because when we moved out rurally, I felt like slowing down. I felt slowing down in myself, you know.

“And so it just made sense to make this an analogue project instead of a digital project. But it felt really wrong to try to create work about my relationship with the natural world while using toxic chemistry. It’s sounds incongruous. And so it was really an ethical and a methodological decision that the medium and the method had to align with the message of the work.”

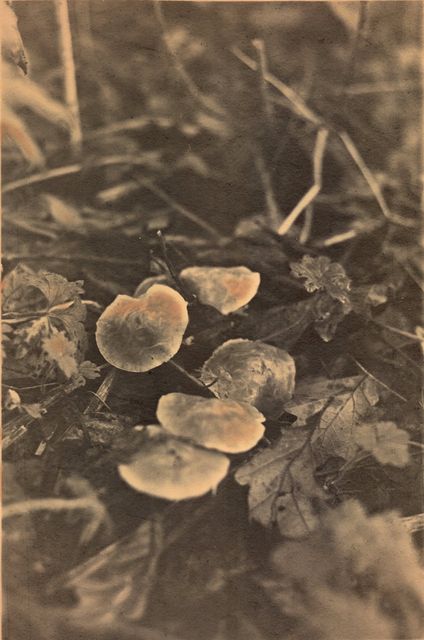

A print featured in Slow Still Life

When researching sustainable analogue processing methods, Savannah found a “growing community of people” online who shared her interests. She also completed a workshop led by photographer Melanie King, who used mint tea to develop photographs.

Through a process of trial and error, the Slow Still Life series began to come together.

“What I’ve done in this exhibition is all of the film is developed with a homemade developer that’s made from basically a tea of brambles, vines and leaves,” Savannah says.

“That tea is steeped overnight and then mixed with vitamin C powder and soda crystals. And that’s my developer, and I’m developing the film with that, and then I’m rinsing it with rainwater.

“With each print, I experimented with different local plants. So some of the developers for the prints are made with rosehip, sometimes nettles, sometimes it’s dock, sometimes it’s brambles. I used apples from my apple tree and sycamore seeds before.

“So I really experimented with trying developers from different plants that I’m able to find in my back garden. That’s how the prints are developed, and then they’re rinsed with rainwater.”

For the final step in the process, Savannah looked to Strangford Lough.

“With printing and film, you have to fix it, because if you don’t fix it, it will just keep changing in the light,” she says.

“I had read about an artist who had used saltwater successfully. I can see Strangford Lough from my living room, so I decided to use that saltwater to make the fixer and give it a deeper connection with the environment.

“So I collected some water from Strangford Lough and I reduced it. Sometimes I reduced it over my fireplace and sometimes I reduced it on the stove if it was not suitable weather for a fire. And basically that makes it its maximum salination, so it really concentrated with salt and that can be used as a fixer.”

A print featured in Slow Still Life

Describing her methodology as “hit or miss”, perfectionist Savannah had to let go of aspirations for technically perfect prints.

An important aspect of creating Slow Still Life involved learning to value the process and find beauty in imperfection.

“There’s one print in the exhibition, it’s a wax cap mushroom, and it was the first successful print I had actually,” she says.

“And I was frustrated because there’s a bit of light: the way that it wasn’t totally fixed when it was exposed to light created different colours on the mushroom. I was really frustrated with myself because I thought: ‘Oh, you know, my process wasn’t totally lightproof.’

“But I shared it with one of those artists who’s also working on sustainable methods and she said: ‘No, that’s what makes it beautiful.’

“And that really was an important reframing for me: that I’m not striving for technically perfect prints, I’m striving to express something through this work and to also demonstrate something through the method.”

The series also features work created using flowers that had been foraged from the Ards Peninsula.

“In this exhibition, you will find anthotype photograms, photographic prints made in a darkroom and images that were transferred onto salvaged windows,” Savannah says.

“Anthotype refers to a photographic process that uses photosensitive extracts from plants. Photogram refers to photographic prints made by placing objects directly on a photosensitive surface. I extracted my own photosensitive emulsion from plants I foraged around my home.

“That’s another component, and that really helps me to learn how to identify plants and have a little bit better understanding of what plants are made of.”

Savannah hopes attendees will leave her exhibition feeling more mindful about the slow moments in nature.

“I’m trying to, I guess, show the value in those ordinary things that feel easily missed,” she says, “and maybe inspire others to slow down as well and think about how they can reconnect with nature and maybe live in a more harmonious way with the world.”

Slow Still Life exhibits at Ards Arts Centre until September 23

[ad_2]