[ad_1]

My mother had four different first names, depending on which language she was speaking at the time. She was Anka in German, Hanka in Polish, Chanka in Yiddish, and after arriving in Australia on a refugee passport in 1949, she adopted the anglicised version of herself, Hannah. Her surname was Altman, although after she married my father, that vestige of her former life disappeared too. The only remnants of her years in Europe were captured in a few black-and-white photographs kept in an old shoebox, hidden away in the hallway cupboard, together with a leather suitcase and tailored winter coat she never wore. As a young girl, I would secretly rummage through these photos, searching for my mother’s story in the anonymous faces I knew no longer walked this earth.

When the ghosts of her past became too much for her to bear, my mother took her own life. I was 21 years old at the time, left to deal with my own ghosts. More than 30 years later, on one otherwise uneventful Sunday afternoon, I tried to resurrect my mother’s past.

I wanted to explain the burnt branches of our family tree to my children, the eldest of whom was turning 21. I had spent my youth running away from my mother’s story. Now, as a mother of the grandchildren she would never know, I felt an urgency to piece together her life. Typing one of the versions of her name into Google – Hanka Altman – up came a link to a photo of her seated in the middle of a group of young men in uniform. She was the secretary for the Jewish Civil Police at Bergen-Belsen’s displaced persons camp in 1946. At 21, she was alone in the world, a survivor of the horrors of the Łódź ghetto, Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen in turn. She was smiling.

There was the reason why. Nandi. Top row, fourth from the left. Handsome and tall, I recognised him immediately from the only black-and-white photo my mother would show me from that hidden shoebox.

“He was the love of my life,” she used to tell me.

And as a young girl, hearing stories of how Nandi made her feel alive again after she had lost her entire world, I kind of fell for him too. She reminisced about how they would go for drives into the countryside on weekends, hiking in the forest, picnicking beside lakes. Licking the wounds of their recent traumas, they spoke headily of a future together, once they could find a country that agreed to take them in as refugees.

The youngest of six siblings, and the sole survivor of her entire family who had all been murdered during the war, my mother had nowhere to go. Nandi had an uncle in America and promised her they would travel there together one day to start a new life. But she told me the love of her life ended up breaking her heart and left Europe without her.

In the photo, she sat looking forward, not knowing how the rest of her life might unfold. She had met Nandi and fallen in love. Although she told me a little about her time in Germany after the war with Nandi, that hopeful moment captured by the camera can never be retrieved. Which leads me back to why I googled her name almost 70 years after the photo was taken. I ached to find out more about their relationship. Who was this man to whom I felt so strangely drawn to?

****

I decided to stalk him online. The same photo that was in my mother’s shoebox appeared on the screen. Five people’s names were identified in the caption underneath, one of whom was Ned, an abbreviation for Ferdinand, Nandi’s real name. He had donated his own copy of the photo to the Holocaust museum in Washington. My heart raced as I ran to tell my children that I had found my mother’s old boyfriend. They had grown up with my curious fascination around Nandi. We quickly looked him up in the phone book and found a number in the US.

“Call him!” my son urged.

We rehearsed how I might introduce myself and explain that I am trying to find out more information about my mother. I would tell Nandi she had spoken so warmly of him. With trepidation, I finally dialled the number. A woman with a heavy eastern European accent answered.

“Hullo?”

“Oh, hello,” I said, my voice shaky. “May I please speak to Ned.”

There was a short pause before she sobbed into the receiver, her anguish reaching right across the Pacific Ocean: “He’s dead.”

I had missed Nandi by two years.

When she calmed down a little, I told her who my mother was and why I was calling.

“I remember Hanka Altman,” she said. I thought I heard a tinge of jealousy rising in her voice, even though decades had passed since they would have met. The two of them used to go away together for weekends, she said.

As we kept talking, I learned the reason Nandi and my mother never ended up together. Something she had never told me. He had left her for Anna, who he ended up marrying in Belsen in late 1946. The same woman I was speaking to on the phone.

There was a pause, before Nandi’s widow added: “He was the love of my life.”

****

In her seminal work On Photography, Susan Sontag writes: “Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself – a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness.” My children’s formative years are heavily documented – each birthday, vacation, trip to the beach. Recording these ordinary events, I have labelled them all, carefully placing them in albums which we hardly ever look at nowadays. It seems that in taking so many photos I was somehow trying to compensate for my mother’s undocumented life.

In my mother’s old shoebox, among the pile of photos, are snaps taken on her voyage aboard the SS Sagittaire from Marseilles, via New Caledonia, arriving in Sydney on 27 July 1949. In one of the black-and-white photographs my mother is wearing a swimsuit as she paddles in the shallows on a tropical beach with four other women. She is holding a half-eaten banana in her left hand. Another snap captures her at the wheel of a convertible, dressed in elegant European style as she stares at the camera. In yet another she is standing on a bridge in some European city I feel I should recognise, wearing a tailored frock and clutching a chic handbag. There are no photos of her family in the shoebox. I don’t know which is worse – to have old photos with images of nameless people you knew were once dear to those you loved, or to have no photos at all. Throughout my life I have tried to imagine what my maternal grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins might have looked like.

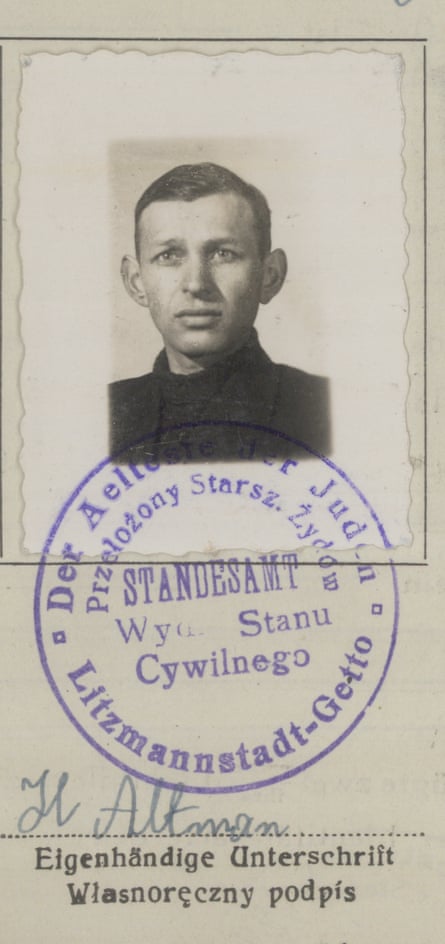

Recently, my husband surprised me with a gift. As I unwrapped it, a photo of a man who looked very familiar stared out at me from the past. I couldn’t place him, but he bore a strange resemblance to my son.

“Who is this?” I asked.

My husband smiled. He had also been stalking the dead. He passed me an official document only recently released from a Polish archive. It was an inmate’s ID card from the Łódź ghetto, dated 11 May 1941. Printed at the top was the name Herszek Altman, born 1911, 43 years of age. My mother’s older brother.

I held the photo of my uncle and gasped for air, feeling like I was drowning in a sea of whispering voices calling out to me from the past. I wondered if it might have saved my mother’s life to have such a tangible link to a loved one.

The people in these photos are now long gone. Yet finally being able to match their names to their faces, I feel like they get to live on just a little longer. “The shortest prayer is a name,” writes Canadian poet Anne Michaels. My mother gazes out from that photo from the displaced persons camp and I wonder what she might ask of me. The faultline between the living and the dead means I can never really know. Perhaps it is simply to ensure that her name, her four names, will not to be lost to history. I do not believe in God, but I am drawn once a year to attend a part of the Yom Kippur service, called Yizkor. Remembrance. The names of those who have died are called out loud by congregants, their presence recreated among the living, if only for a moment. I speak my mother’s name quietly, offering her memory up to strangers. The echoes haunt the synagogue like an incantation, returning her to me in some small way. I could not bear to lose her twice.

[ad_2]