[ad_1]

A new group exhibition at New York’s International Center of Photography showcases the work of three photographers produced during far-flung residencies. One journeyed to the islands of Guadeloupe, another to the borderlands of France, and the other to New Orleans. Each distinctly disparate project receives its own section, but the show has an overall cohesion. Although all three artists used different methodology and approaches, a throughline resounds; in his own way each was gracefully, soulfully reflecting the human condition and spirit.

“Immersion” is on view until January 8, 2024, and documents Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks, and Vasantha Yogananthan’s sojourns. “I think all of us are intuitive in terms of the way that we work,” Halpern said. “I was trying to respond to the feeling of the place.” Overall, the experience is a celebration of resilience, but it can also unflinchingly explore some hard truths.

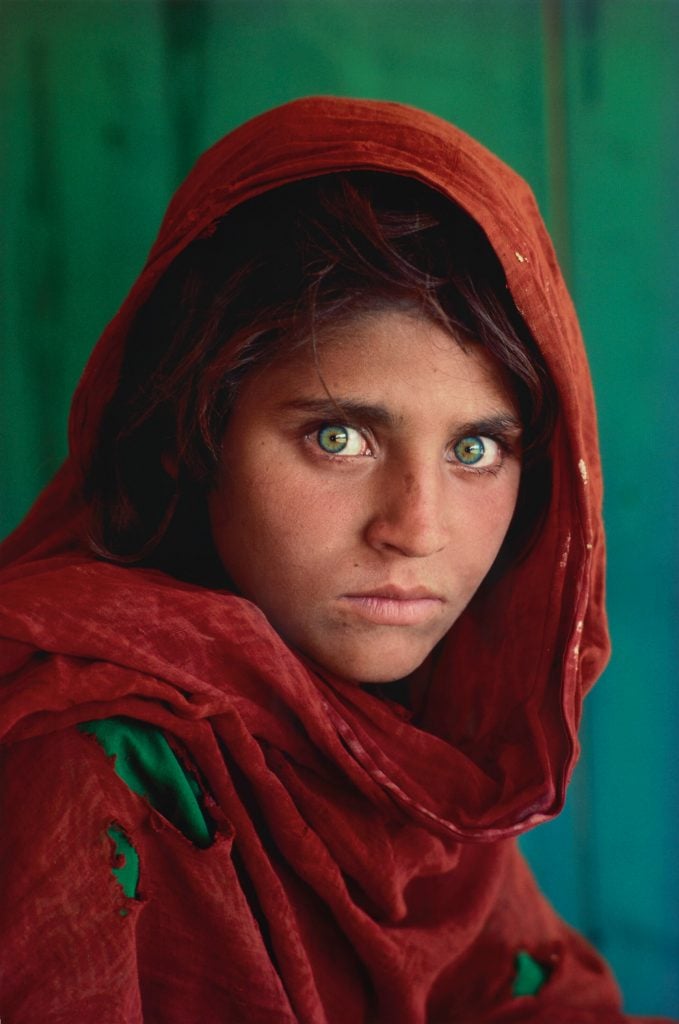

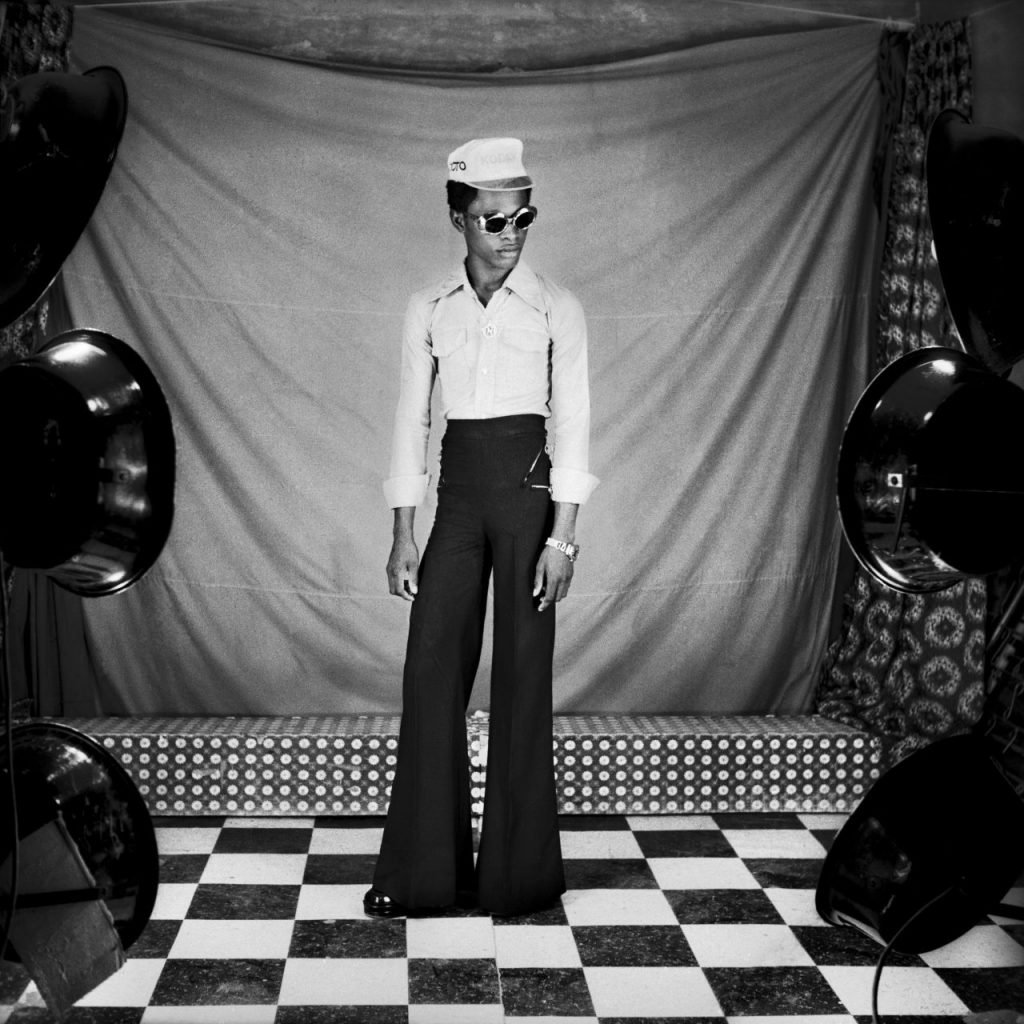

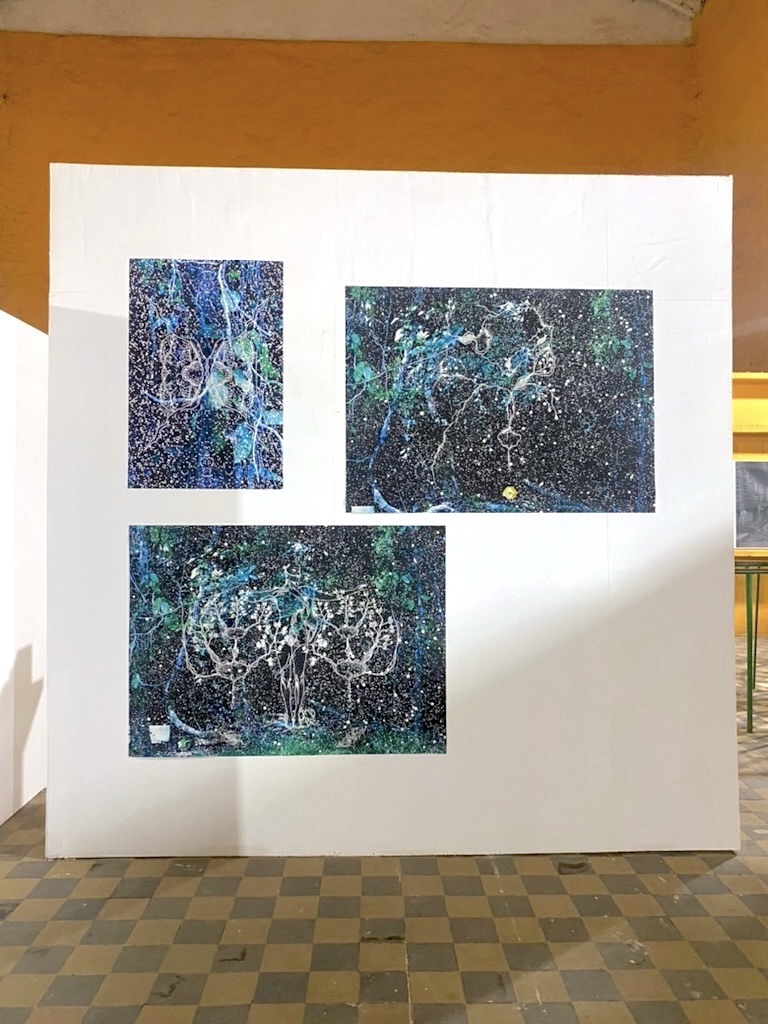

Vasantha Yogananthan, Untitled from “Mystery Street,” (2022). © Vasantha Yogananthan

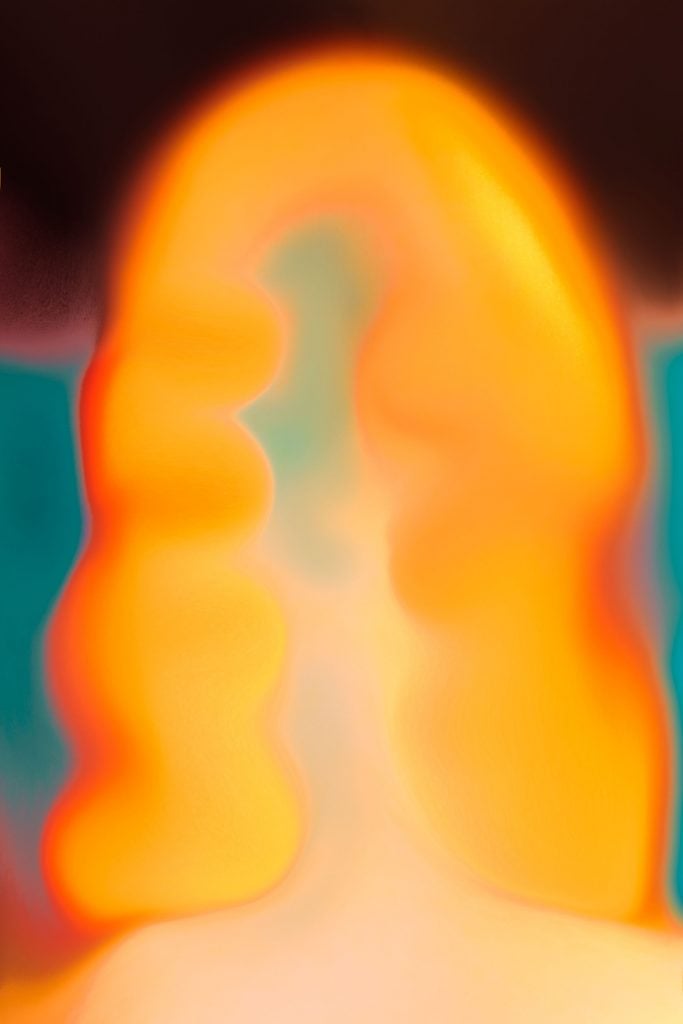

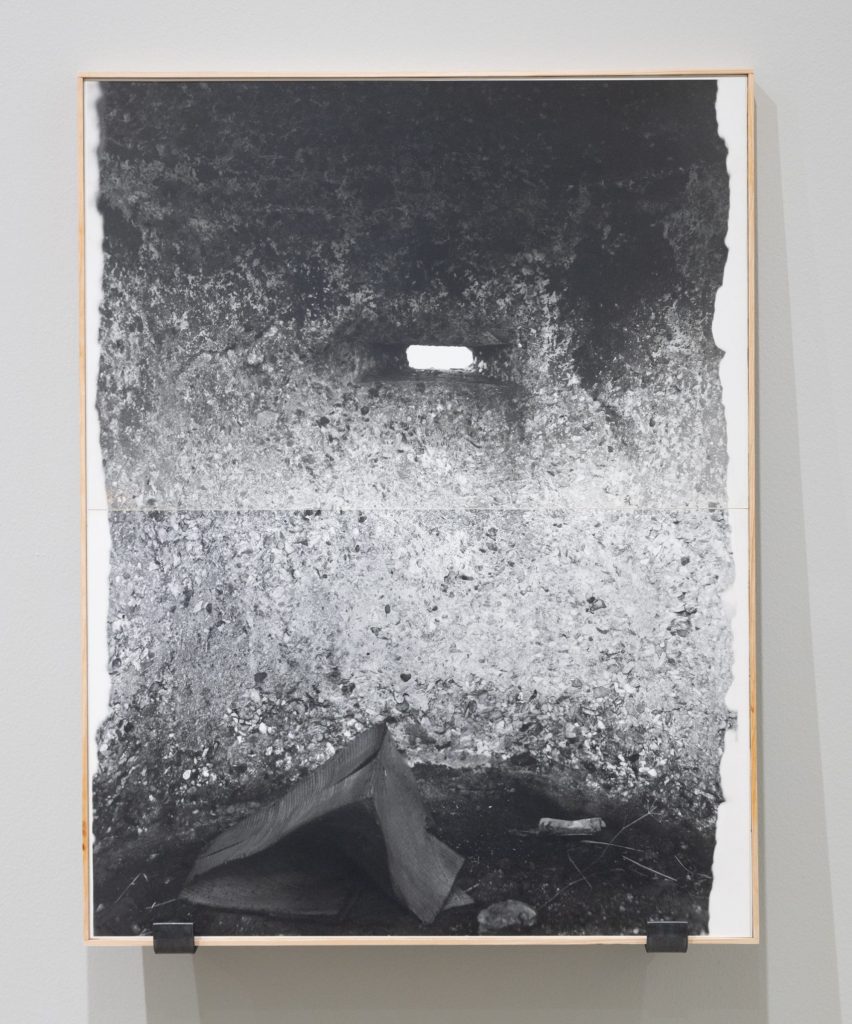

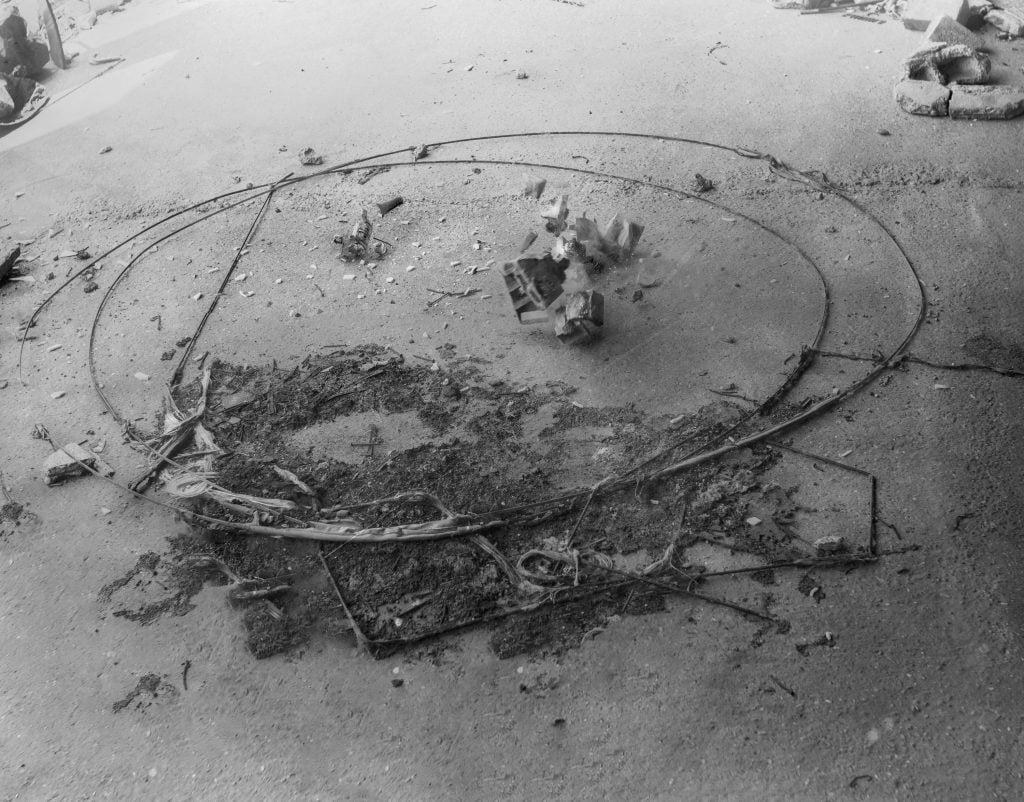

Yoganthanan delivered colorful childhood Louisiana reveries. Halpern reflected on the reverberations of the colonial period and the slave trade in Guadeloupe. Meeks’s somber and oddly beautiful, mostly black-and-white series delves into immigrant crossings (made during his own personal crossroads). He captures displacement and human desperation in landscapes and still lifes without portraying people. Some of his images are so abstract they look like the surface of the moon.

One of Meeks’s abstract takes on landscapes in an Installation view, “Immersion: Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks, and Vasantha Yogananthan,” International Center of Photography, New York, September 29, 2023–January 8, 2024. Image: © Jeenah Moon for ICP.

Meeks explained, “As photographers, as much as we read the world, I think we’re also projecting. I was always projecting my own state of mind.”

Immersion is also the name of the French-American Photography Commission that sponsored the residencies created by the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès and presented in collaboration with ICP and the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson. At the heart of the project is unbridled creativity. “It’s very open,” said Laurent Pejoux, the director of the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès at last week’s busy vernissage. “They’re totally free to choose the subject. We don’t want to impose the project to the photographer. La liberté is an important notion in France. That’s why we support projects like this where the liberty was total.”

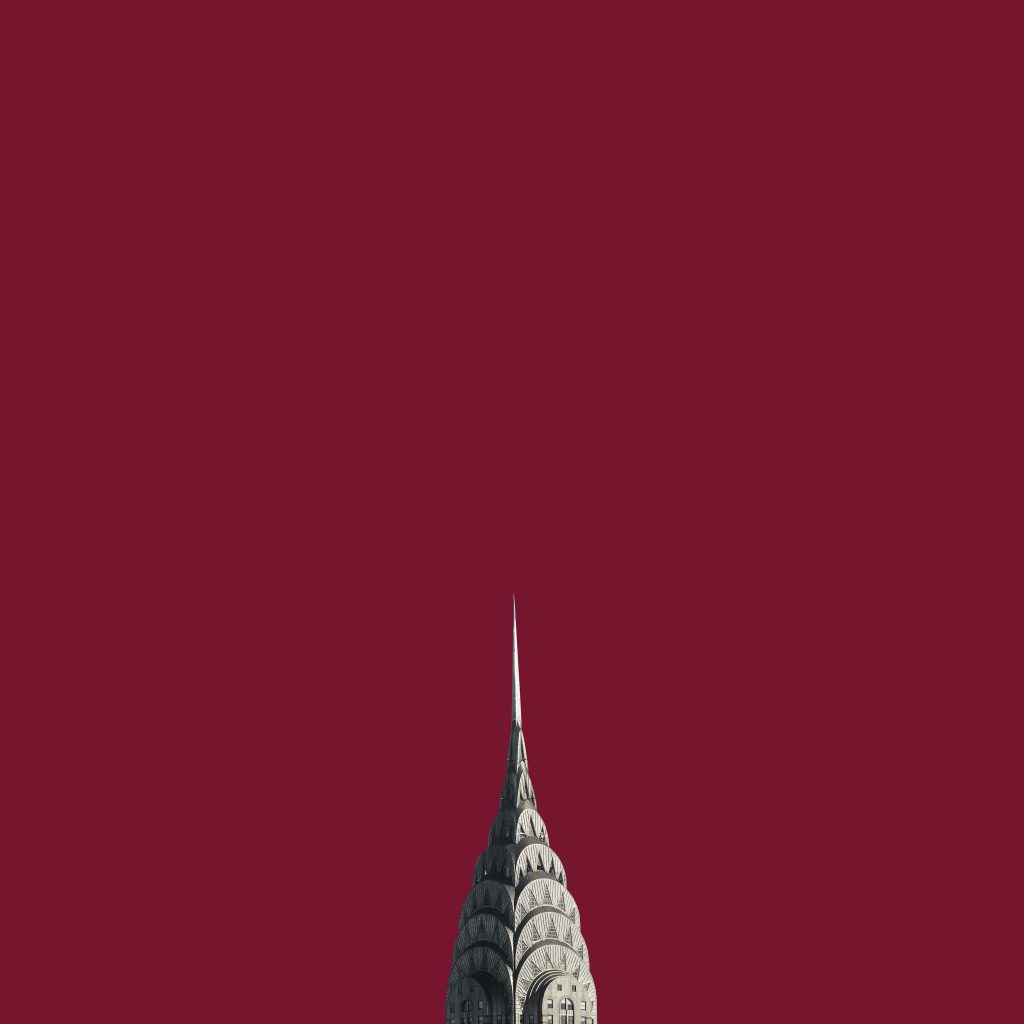

Halpern recreated a defaced bust of Christopher Columbus in this installation view, “Immersion: Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks, and Vasantha Yogananthan,” International Center of Photography, New York, September 29, 2023–January 8, 2024. Photo: © Jeenah Moon for ICP.

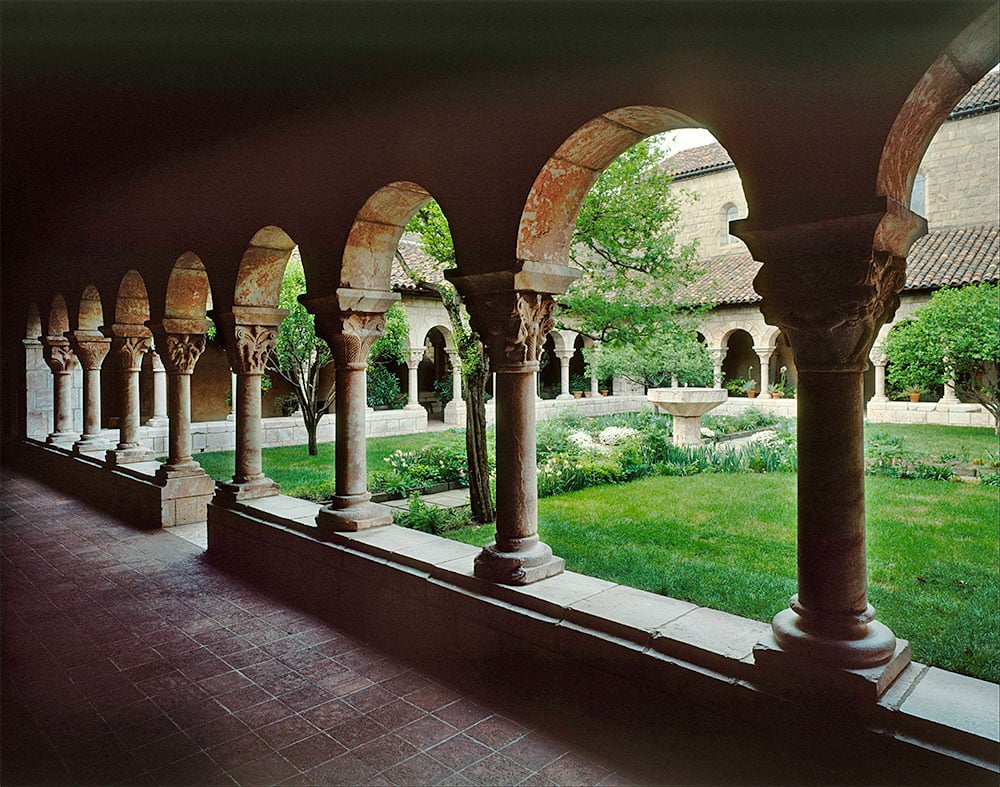

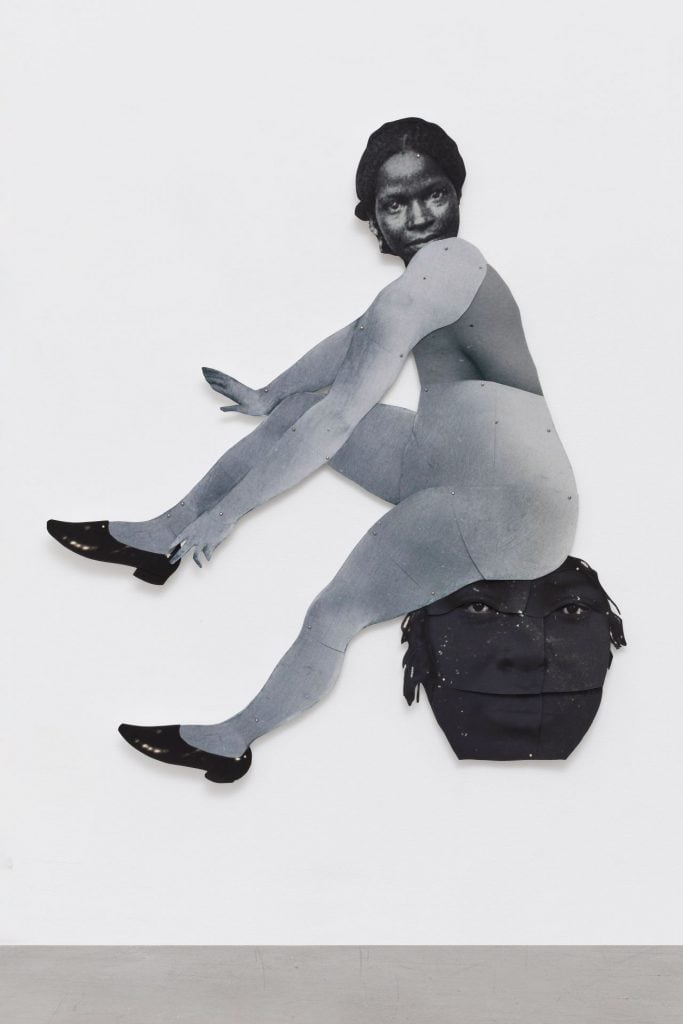

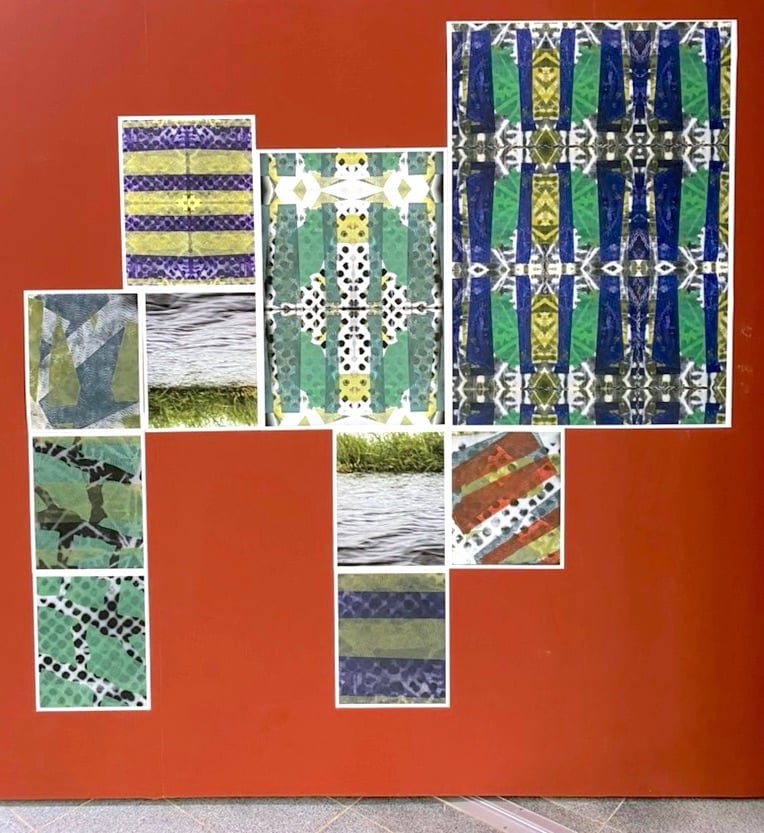

Each of the photographers also included a sculptural element to their project. Halpern recreated a defaced bust of Christopher Columbus and included flickering video screens depicting an invasion of cruise-ship tourists, Yogananthan gathered his images into an elegant, large-scale 3-D assemblage, while Meeks powerfully punctuated his section with rusted barbed wire and makeshift campfire grills sourced from the borderlands’ camps. We caught up with each on the evening of the opening for a brief walkthrough.

Vasantha Yogananthan

“Mystery Street”

Installation view, “Immersion: Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks, and Vasantha Yogananthan,” International Center of Photography, New York, September 29, 2023–January 8, 2024. Image: © Jeenah Moon for ICP.

New Orleans is a subtle character in your series. The images don’t scream that locale. There’s no crawfish clichés here.

I wanted to approach the city as a fictional space. I like that the pictures are very fragmentary. They don’t really show the landscape. For someone who knows New Orleans, maybe you feel the city—the colors, the light, the atmosphere. The project is about childhood. It can be from any place or anywhere in the world.

What was your process?

I picked the summertime to go because school was over and the children would be free all day long. There was a lot of boredom, as the days are longer. At first I was thinking that the project would be about playing. And then I got more interested about what happens before and after game time—these moments where the children are together it seems at first that nothing is happening, but maybe this is where everything is happening. After weeks being immersed with one group of kids, it almost felt dystopian, where the adults have left and the children are running the city and they’re free to do whatever they’d like to do. I really like that idea, of them owning the space.

Vasantha Yogananthan, Untitled from “Mystery Street” (2022). © Vasantha Yogananthan.

One image that is very striking is the child with the hula hoops on the stairs.

Yeah, this picture was shot in a summer camp. For five weeks I would go there in the morning and stay all day long. Most days, nothing worth photographing would happen. One has to be very patient in observing kids. At some point, if you’re patient enough, and if you’re kind, and if you care, something is going to happen. Henri Cartier-Bresson coined ‘the decisive moment,’ meaning, ‘Hey, I was there, like, at the exact right time, right place, and I clicked a picture that kind of summarized what the place is about.’ My feeling was the opposite, because I was there for five weeks in the summer camp and made maybe five good pictures happen. Meaning that most of the time, nothing happens. The photographer, by just being there—and most of the time not taking any pictures—is taking in a lot of information.

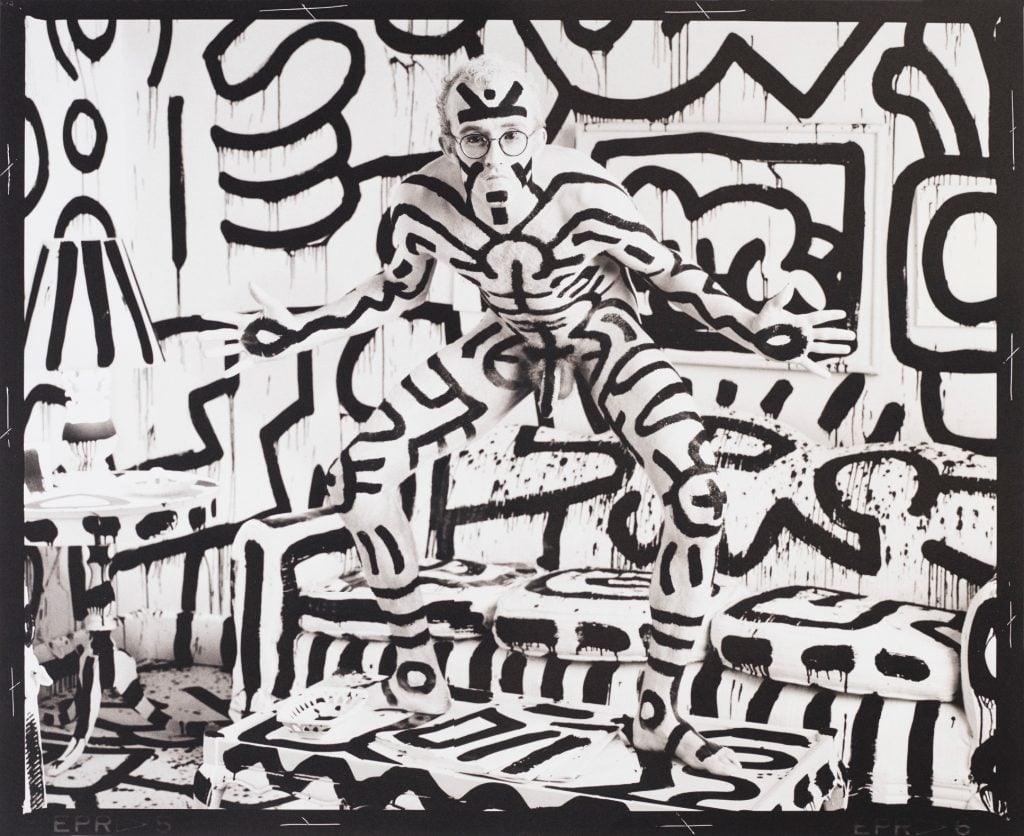

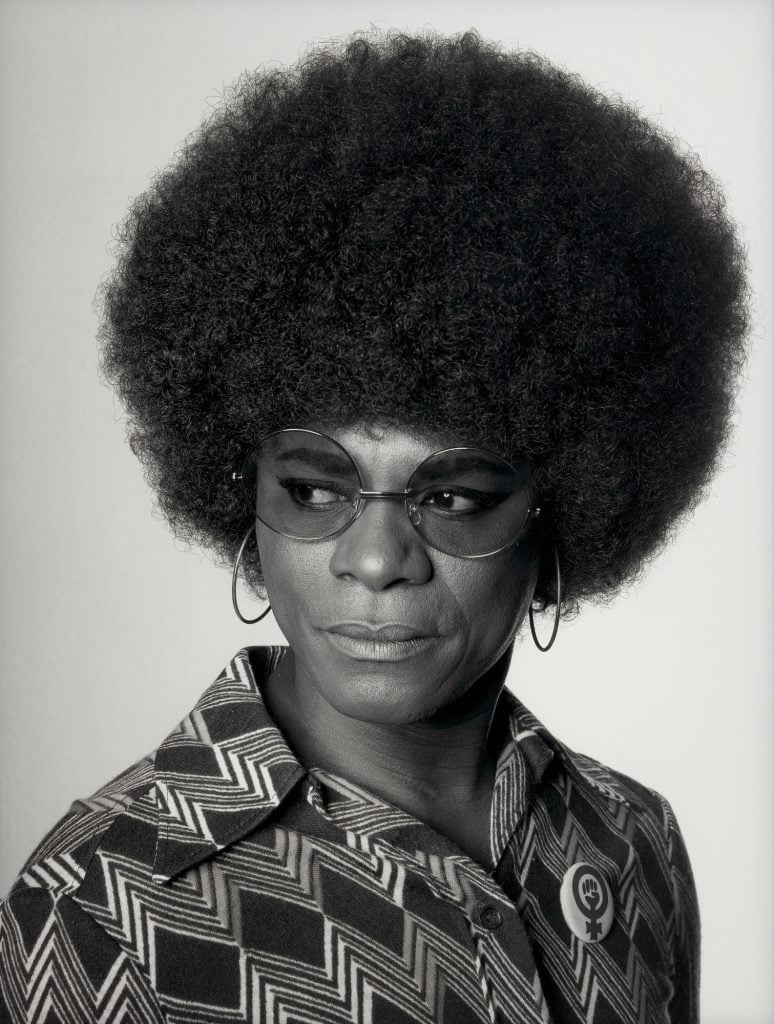

Gregory Halpern

“Let The Sun Beheaded Be”

Gregory Halpern, Untitled from “Let the Sun Beheaded Be” (2019). © Gregory Halpern

What drew you to the island in the first place?

As a 10-year-old, I went on a vacation to Guadeloupe. What I remembered was the total isolation from the place itself as a tourist. I’m fascinated by the idea of not doing that with this project and thinking about how this is a place of both tourism but also extreme pain, in terms of its history and its relationship to colonialism and the slave trade. I did a lot of research. I thought people would be very resistant to me as a white American, but they were incredibly welcoming. I talked about the thing that isn’t talked about. Tourists come here and don’t interact with the local culture. When the elephant in the room gets addressed, then people are very happy to talk to you as an outsider. People were like, ‘Oh, that’s so interesting that you want to talk about the actual culture and history and what it’s like to be here, not just as a tourist.’ In 1815, Napoleon abolished slavery, but then reneged on it, and in 1848 it was officially undone.

Can you tell me about the video component?

Tourists will come off of these cruise boats and they basically flood the main city, Pointe-à-Pitre, for like, three hours. They basically go and they photograph the locals who are selling vegetables and fruits, and then they get back on the boat. And to me it was like this guy, he’s photographing this woman. He’s sneaking up because she doesn’t want her photo taken. She’s holding up a bowl to protect her face. For me, it’s all about politics and battle and colonialism. And it’s also kind of about me, like a self-portrait, because I’m basically a tourist and outsider.

Raymond Meeks

“The Inhabitants”

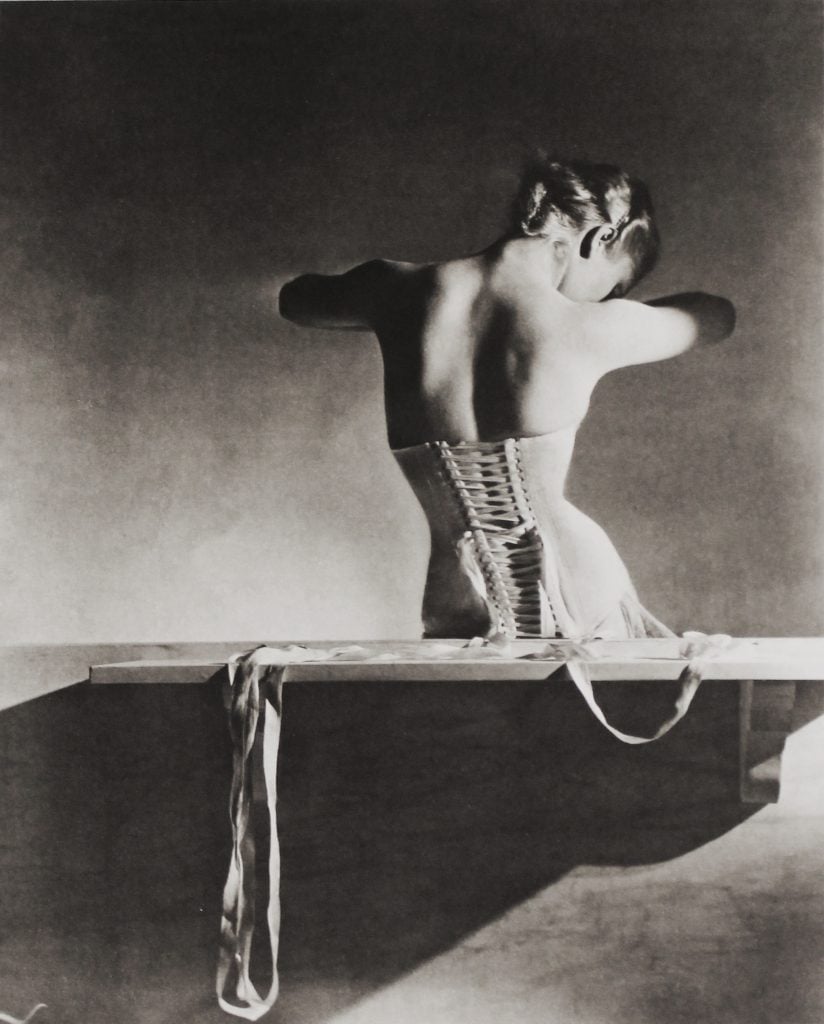

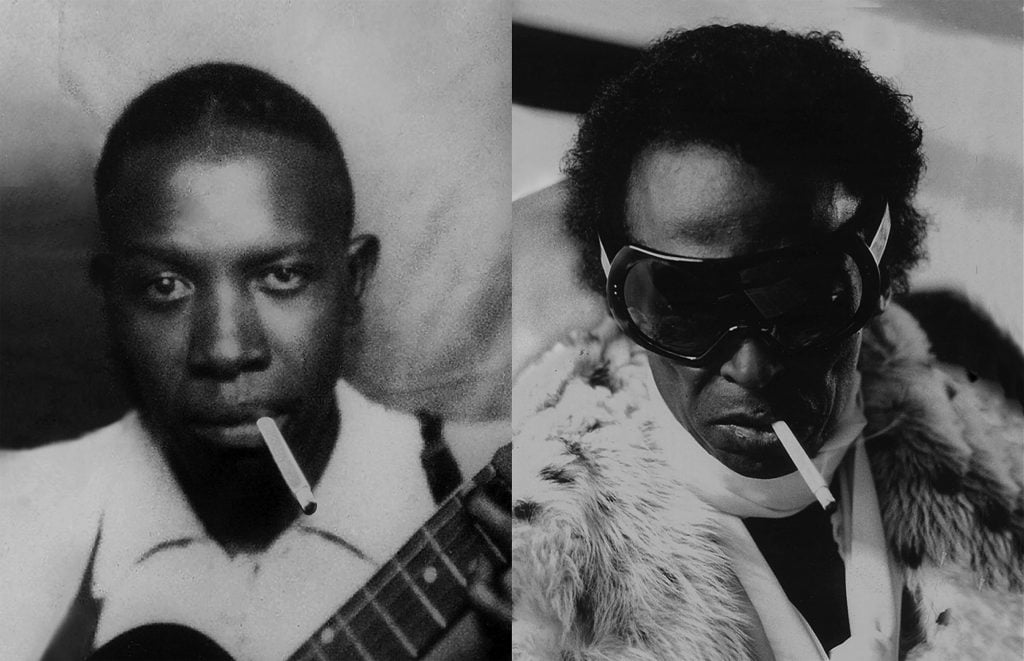

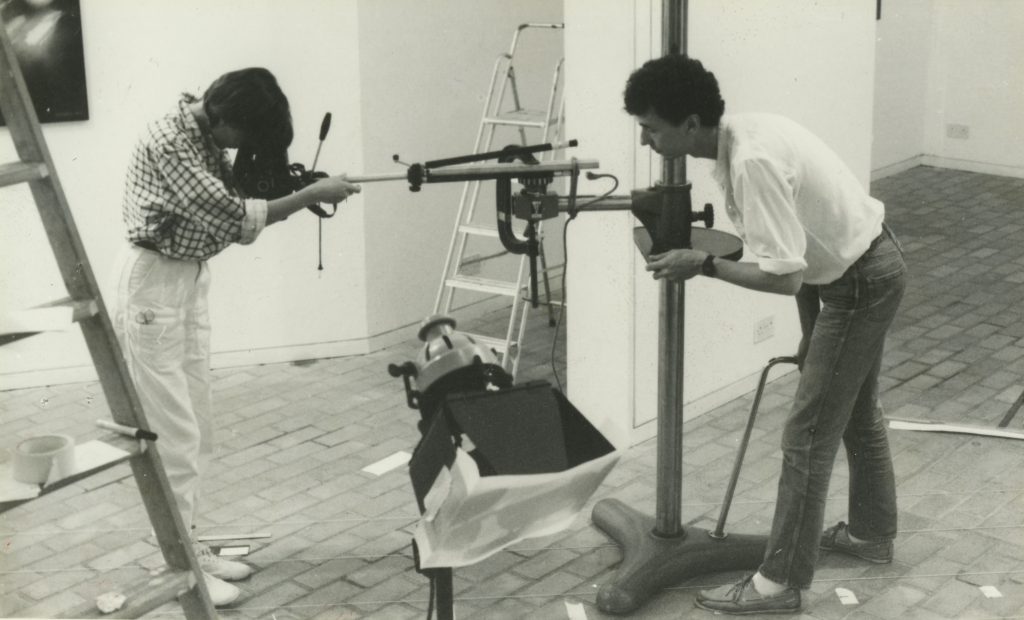

Raymond Meeks, Untitled from “The Inhabitants” (2022). © Raymond Meeks

This was a very complex journey for you.

Calais is the center of the refugee crisis in Europe. By the time I arrived, I found myself in a state of displacement. All of my stuff was going into storage, and a relationship of ten years had ended and I didn’t have a home. So going to France kind of put me in a state of searching and of longing and wanting to create a sense of place, some sense of home. I think it put me on a level of searching for discovery and empathy and a compassion for what that experience is. I was in southern France for three months; I was in northern France for three months. So it’s just trying to imagine these borderlands. I’m making pictures and then I’m bringing them back and I’m crafting a story. I’m trying to understand what the work is trying to convey, what the work wants to be, what it wants to speak of.

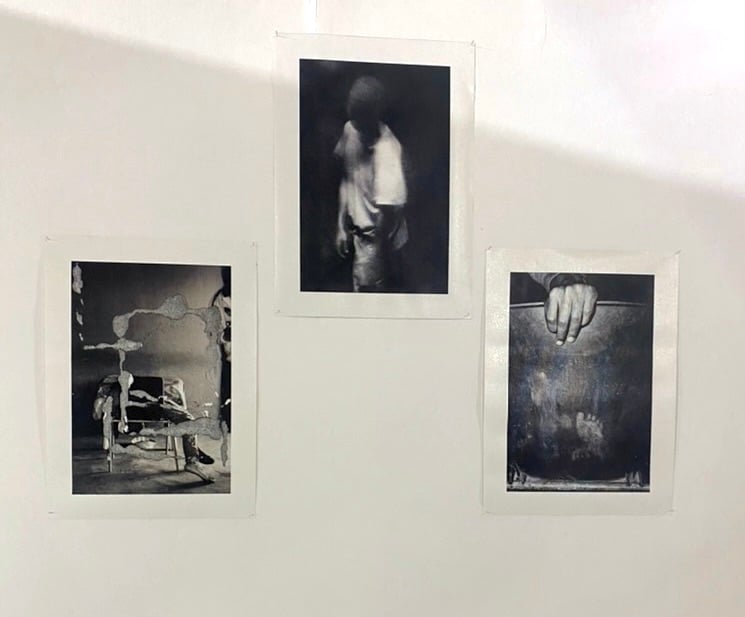

Installation view, “Immersion: Gregory Halpern, Raymond Meeks, and Vasantha Yogananthan,” International Center of Photography, New York, September 29, 2023–January 8, 2024. Photo: © Jeenah Moon for ICP.

There’s such brutalist imagery, like the cement with rebar poking through. It’s a rough landscape, but also beautiful. Nature seems to prevail. A lot of these structures look ancient. This work is about refugees, but none are depicted.

I had planned on doing portraits. I volunteered with an organization called Care4Calais that provided basic needs to refugees who were holding in Calais. And by doing so I became friends with quite a few of them. At that point I realized I didn’t want to do portraits. Because as I was interacting with them I realized I’m looking at them as a subject, not engaging with them as a human being. And I’m missing out on so much by thinking about what a picture of them might bring to my project. And that just felt exploitative to me. So I decided just to be present and to sort of try to carry the essence of their stories with me as I make pictures.

The installation of your show is so beautiful, from the excavation elements of found objects to the framing and how some photos are broken into grid-like quadrants.

With the sponsorship of Hermès, I had ultimate possibilities. I could have large silver gelatin prints made and the best framing, which would be a dream. Like, all this was a possibility for me. But that possibility also created a lot of confusion. I realized I don’t need to buy anything. Coming from this experience where, where human beings are just trying to make do with the things that are left behind, that they find, that are handed down to them—I just thought, like, I don’t want to consume more things. The constraint was that I will make use of what I have, I will make use of the wood, I will make everything myself. It became part of petitioning or prayer or like a meditation—and also just being deeply engaged in the creative process.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

[ad_2]